Stack the Flags 2020

Contributors: @oceankoh, @milotruck, @NyxTo

Contents

- Overview

- Cloud

- Cryptography

- Forensics

- Internet of Things

- Mobile

- Open Source Intelligence (OSINT)

- Social Engineering

- Reverse Engineering

- Web

Overview

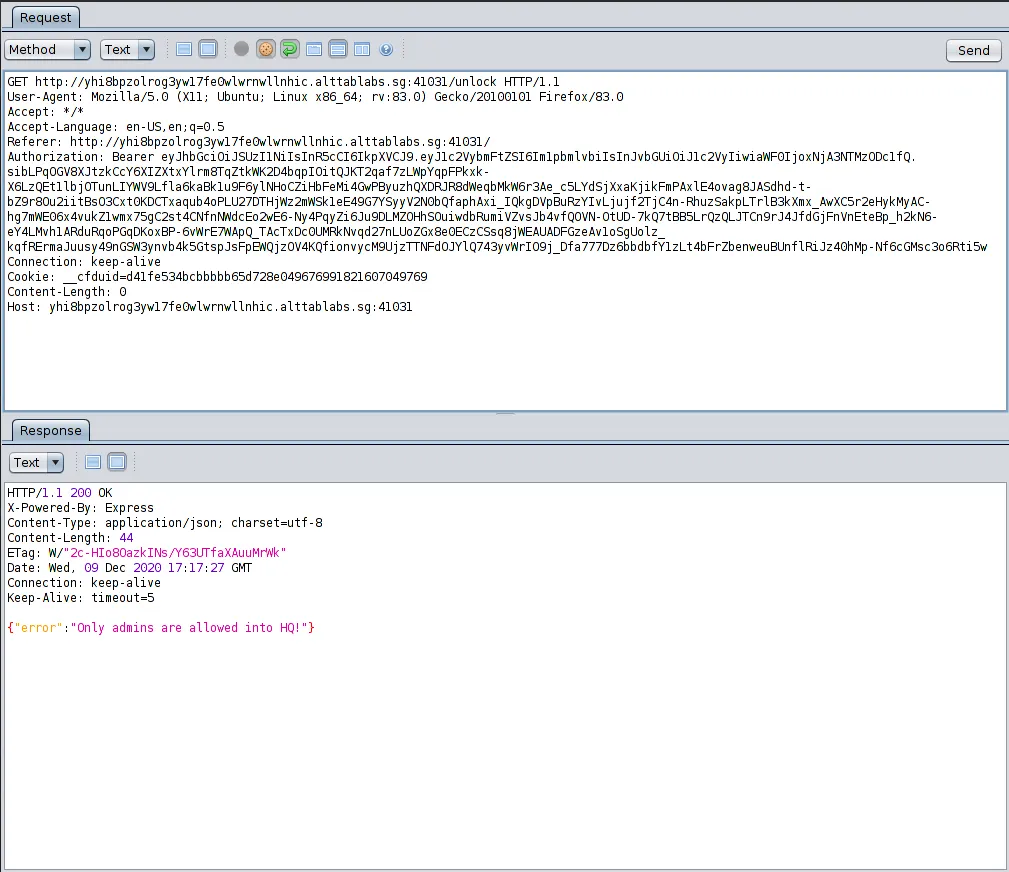

Team Name: ItzyBitzySpider

Position: 3

Score: 37754

Cloud

Find the leaking bucket!

Points: 978

Solves: 12

Challenge Description

It was made known to us that agents of COViD are exfiltrating data to a hidden S3 bucket in AWS! We do not know the bucket name! One tip from our experienced officers is that bucket naming often uses common words related to the company’s business.

Do what you can! Find that hidden S3 bucket (in the format “word1-word2-s4fet3ch”) and find out what was exfiltrated!

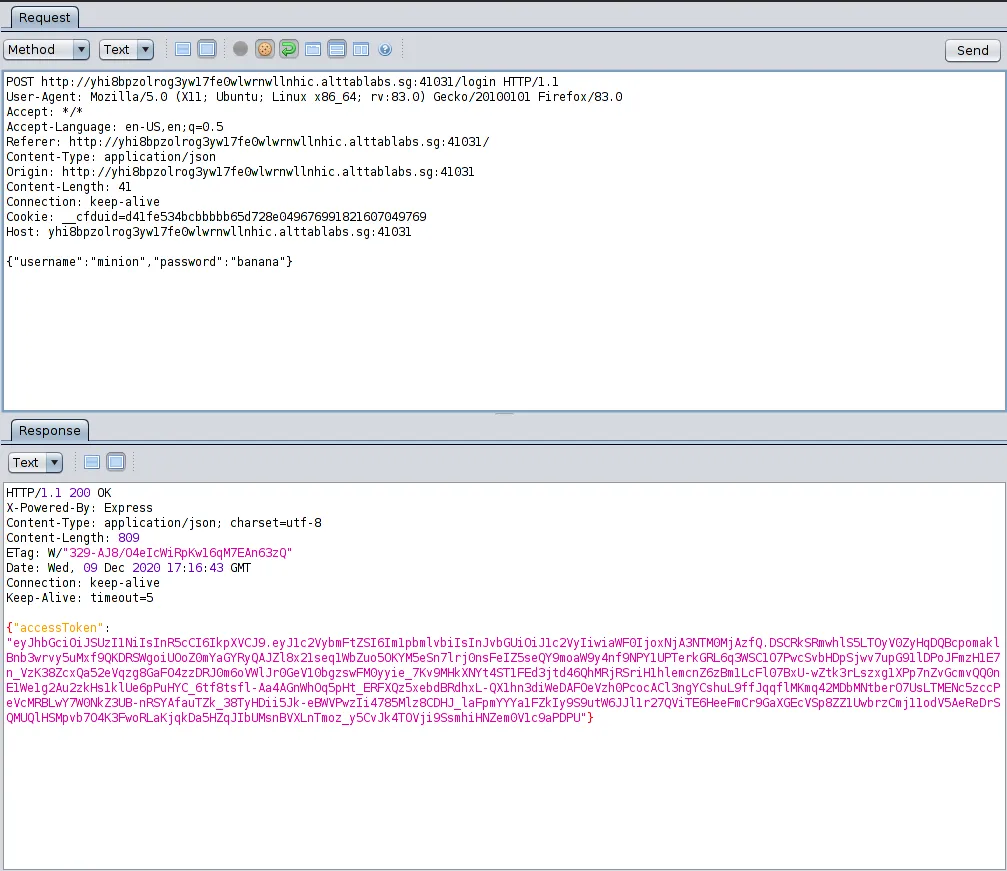

Solution

There doesn’t seem to be any obvious way to find out the leaking bucket. So we decided to brute force to find out. With only 2 words to guess, brute force doesn’t seem unreasonable, taking worst case of \(n^2\) tries where \(n\) is the number of words in our wordlist.

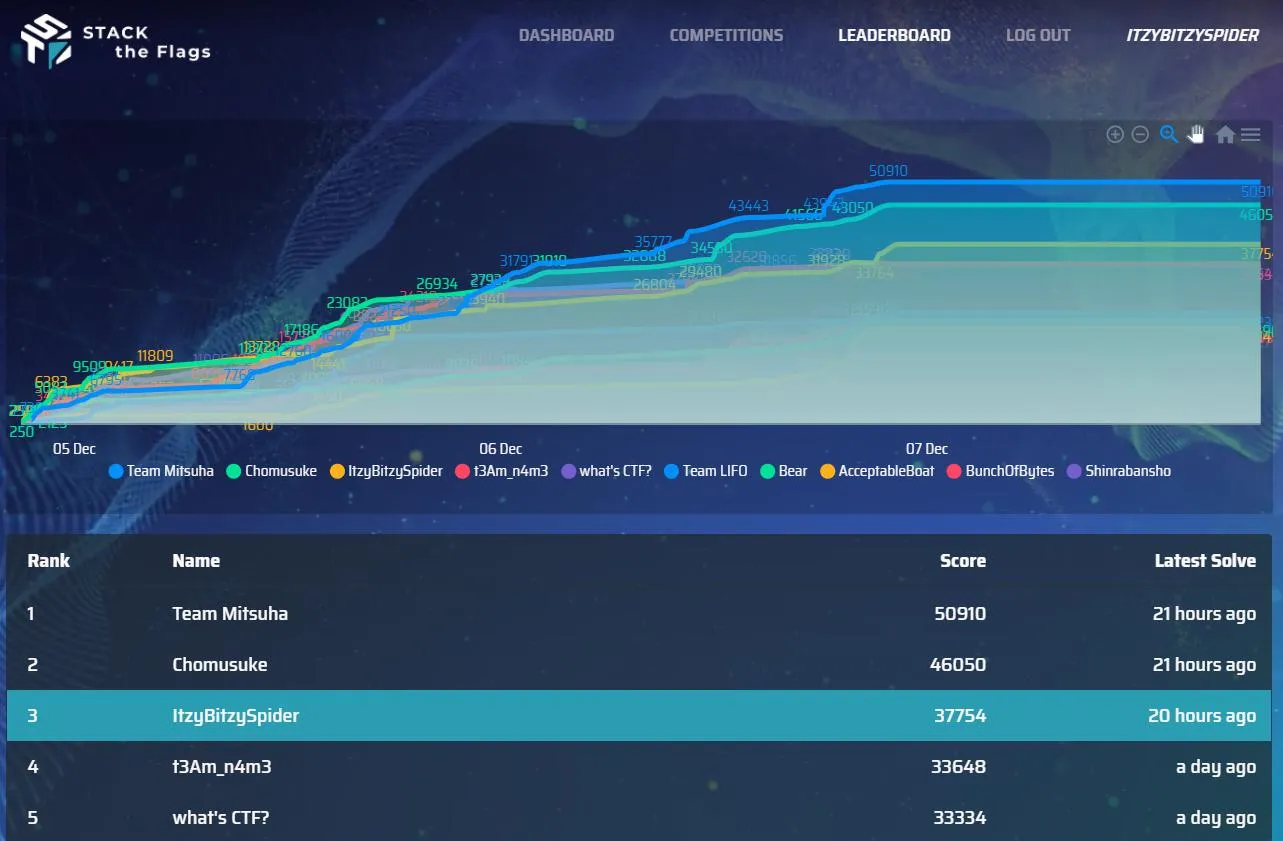

Visiting the company site, we are greeted with a word cloud. The most obvious solution was to use these words in the word cloud, however, we couldn’t find the bucket with that alone (if only it were that simple…)

At this stage, we thought we needed to come up with our own words. To facilitate this I uploaded the script to our team EC2 instance which we set up in preparation for this ctf. There, we just kept adding words that we thought of including text from images on the website. With the new wordlist, we ran the script again.

This allowed us to find the bucket: think-innovation-s4fet3ch

While the script was running, we managed to confirm with admin that all words could be found on the website. But by then, we had already found the bucket. This is thanks to one of our team members deciding to add in words from the quote by Steve Jobs.

Using aws cli, we can easily view the contents of the bucket with the command:

aws s3 ls s3://think-innovation-s4fet3ch

For which we get the following output

2020-11-17 23:59:54 273804 secret-files.zip

Promising… Seems like we found the bucket. Again using aws-cli, we download the files with

aws s3 cp s3://think-innovation-s4fet3ch/secret-files.zip ./

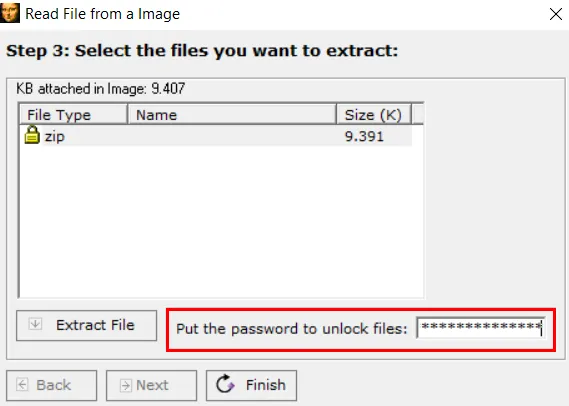

But our job is not done yet. When we try to unzip the files, we are prompted for a password (nani???). Immediately we thought of cracking the zip. With a few simple commands, we already got JTR brute forcing the zip. But after running it for a few second, we already sorta knew this wasn’t the solution. If JTR wasn’t able to insta-crack it with rockyou.txt, it’s quite safe to say the password is strong. However, we weren’t out of options just yet. While attempting to unzip, we also see that there are 2 files in the zip.

ERROR: Wrong password : flag.txt

ERROR: Wrong password : STACK the Flags Consent and Indemnity Form.docx

Why is there an extra document there??? Looks like it was left there on purpose. It is a file that participants under 18 must fill up to join the CTF, we encountered it during registration, and we knew we could download a copy. So we know

- The zip contains 2 files with both encrypted

- The password is relatively resistant to brute force

- We have an unencrypted copy of one of the files

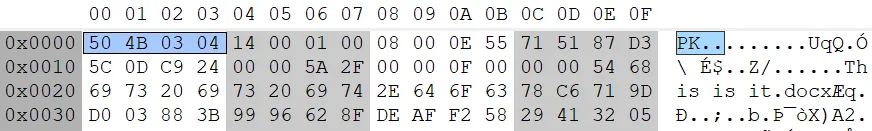

Surely, this having access to one of the files must help right? And indeed it does. Knowing the plaintext of one of the files makes the zip vulnerable to a plaintext attack. We can use pkcrack to perform this attack. For this to happen, we also need to ensure that our plaintext is compressed in the same way as the encrypted zip. Initally, we tried to use Ubuntu default archive manager, and that didn’t work. Next we tried zipping it from the cmdline using:

zip -r known.zip STACK\ the\ Flags\ Consent\ and\ Indemnity\ Form.docx

Within a few seconds, pkcrack gives us an unencrypted zip file which contains our flag.txt.

Flag: govtech-csg{EnCrYpT!0n_D0e$_NoT_M3@n_Y0u_aR3_s4f3}

Cryptography

Can COViD steal Bob’s idea?

Points: 960

Solves: 16

Challenge Description

Bob wants Alice to help him design the stream cipher’s keystream generator base on his rough idea. Can COViD steal Bob’s “protected” idea?

Method

To handle the .pcapng file, we open it in WireShark. We can extract the following text:

p = 298161833288328455288826827978944092433

>g = 216590906870332474191827756801961881648

>g^a = 181553548982634226931709548695881171814

>g^b = 64889049934231151703132324484506000958

Hi Alice, could you please help me to design a keystream generator according to the file I share in the file server so that I can use it to encrypt my 500-bytes secret message? Please make sure it run with maximum period without repeating the keystream. The password to protect the file is our shared Diffie-Hellman key in digits. Thanks.

As stated in the message, this is the usual set-up for a Diffie-Hellman key exchange, and we are given the publicly-known parameters. The challenge also mentions that the flag is just a number wrapped in the flag format govtech-csg{numeric-string}, so we can safely take it that the shared key, g^(ab), is required.

The most efficient way to solve the Diffie-Hellman problem is to take the discrete logarithm, in particular to find what the private exponents, a and b are. To do this we utilise the discrete_log function in the SageMath software. As the given parameters do not have too large an order of magnitude, it would not take too long to execute the program.

Since the modulus, p is prime, we take the parameters as elements on the Galois Field of order p.

p = 298161833288328455288826827978944092433

g = 216590906870332474191827756801961881648

g_a = 181553548982634226931709548695881171814

g_b = 64889049934231151703132324484506000958

F = GF(p)

a = discrete_log(F(g_a), F(g))

b = discrete_log(F(g_b), F(g))

pow(g, a*b, p)

After several seconds of running the above in SageMath, we get the shared key pop out, 246544130863363089867058587807471986686. Simply wrap it in the required flag format.

Flag: govtech-csg{246544130863363089867058587807471986686}

Forensics

Walking down a colourful memory lane

Points: 992

Solves: 6

Remarks: First Blood

Challenge Description

We are trying to find out how did our machine get infected. What did the user do?

Memory Analysis

We are given a .mem file (Memory dump). We can use the premier tool for memory forensics volatility. In my 2 weeks of memory forensics experience, I found that as volatility3 is rather new, I prefer to stick to volatility (python2) due to the wealth of available plugins. Note that on my machine, I’ve set up an alias vol for python vol.py.

For those who are using volatility for your first time, the format for each command is vol -f <file> <plugin/command>

From previous CTFs, I follow a standard procedure (assuming it is a Windows machine which is typical of many CTFs), running imagescan then pslist. This is a very good starting point as it gives an idea of the machine profile. Think of profiles as a type of Windows machine (ie Windows7, WindowsXP, etc).

$ vol -f forensics-challenge-1.mem imageinfo

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6.1

INFO : volatility.debug : Determining profile based on KDBG search...

Suggested Profile(s) : Win7SP1x64, Win7SP0x64, Win2008R2SP0x64, Win2008R2SP1x64_24000, Win2008R2SP1x64_23418, Win2008R2SP1x64, Win7SP1x64_24000, Win7SP1x64_23418

.

.

.

We can choose the first suggested profile, then run pslist to check that the profile chosen works well. Remember to append --profile=<chosen_profile> in each volatility command now. pslist would return the entire process list.

$ vol -f forensics-challenge-1.mem --profile=Win7SP1x64 pslist

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6.1

Offset(V) Name PID PPID Thds Hnds Sess Wow64 Start Exit

------------------ -------------------- ------ ------ ------ -------- ------ ------ ------------------------------ ------------------------------

.

.

.

0xfffffa80199e6a70 chrome.exe 2904 2460 33 1694 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:20 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801a1d5b30 chrome.exe 852 2904 10 170 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:20 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801998bb30 chrome.exe 1392 2904 10 274 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:20 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801a91d630 chrome.exe 692 2904 13 225 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:20 UTC+0000

0xfffffa8019989b30 chrome.exe 1628 2904 8 152 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:21 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801a84cb30 chrome.exe 1340 2904 13 280 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:24 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801acbeb30 chrome.exe 1112 2904 14 251 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:27 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801acd8b30 chrome.exe 272 2904 14 239 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:27 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801acd1060 chrome.exe 1648 2904 13 227 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:28 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801acedb30 chrome.exe 3092 2904 13 212 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:28 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ad0eb30 chrome.exe 3160 2904 15 286 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:29 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ad3cb30 chrome.exe 3220 2904 15 295 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:30 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ad3ab30 chrome.exe 3240 2904 13 218 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:30 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ad8d060 chrome.exe 3320 2904 13 218 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:32 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ad9eb30 chrome.exe 3328 2904 13 231 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:33 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801addfb30 chrome.exe 3380 2904 13 304 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:34 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ad9ab30 chrome.exe 3388 2904 13 283 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:34 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ae269e0 chrome.exe 3444 2904 13 231 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:38 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ae2e7d0 chrome.exe 3456 2904 12 196 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:42 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ae63060 chrome.exe 3568 2904 12 222 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:44 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801ae89b30 chrome.exe 3584 2904 9 173 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:45 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801aed8060 notepad.exe 3896 2460 5 286 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:52 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801aeb5b30 chrome.exe 2492 2904 12 171 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:58 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801af22b30 chrome.exe 1348 2904 12 171 1 0 2020-12-03 09:10:59 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801af63b30 chrome.exe 3232 2904 12 182 1 0 2020-12-03 09:11:00 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801af9d060 chrome.exe 4192 2904 12 168 1 0 2020-12-03 09:11:02 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801afaf630 chrome.exe 4268 2904 12 171 1 0 2020-12-03 09:11:04 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801afa6b30 chrome.exe 4324 2904 14 180 1 0 2020-12-03 09:11:04 UTC+0000

0xfffffa801afbeb30 chrome.exe 4380 2904 12 179 1 0 2020-12-03 09:11:04 UTC+0000

From experience, we can see 2 suspicious processes notepad (commonly used as a target in other CTFs) and chrome (exceptionally large number of chrome processes). I decided to explore chrome first as it is very suspicious to have such a large number of Google Chrome processes.

Analyzing chrome.exe

To analyze a Google Chrome history, we can use the filescan and dumpfiles plugins, followed by using sqlitebrowser to view the chrome history. More can be read up on part 9 in this writeup.

Alternatively, we can install the chromehistory plugin from https://github.com/superponible/volatility-plugins. If your volatility was compiled from source, you can copy the plugin files into volatility/volatility/plugins rather than passing the --plugins=<directory> argument. This makes it easier to install plugins though it can get very messy if you wish to uninstall them so I only advise to do this if you really want the convenience of installing plugins which you KNOW work.

Most of the websites here are fluff as one could tell from random Google searches and going to STACK conference website homepage. However, 2 lines caught my attention:

$ vol -f forensics-challenge-1.mem --profile=Win7SP1x64 chromehistory

.

.

.

8 http://www.mediafire.com/view/5wo9db2pa7gdcoc/This_is_a_png_file.png/file This is a png file.png - MediaFire 3 0 2020-12-03 09:10:50.055213 N/A

24 http://www.mediafire.com/view/5wo9db2pa7gdcoc/ This is a png file.png - MediaFire 3 0 2020-12-03 08:24:50.579952 N/A

A PNG file from mediafire. Looking back at the challenge name, we realize that colors could refer to images like this one.

Analyzing the PNG

If we look at the PNG - well - you can’t really see it as it is tiny. In case the image is too hard to see, I’ll describe it: a small line of colored then black pixels. Initially, I thought it was colored text in a terminal. However, after downloading the image, further inspection by viewing image properties showed that it was a 64x1 pixel image.

After some thought, I noticed that it was a line of colored pixels, followed by a line of black pixels. The RGB values of black is (0,0,0). We can consider the fact that the RGB values of each pixel correspond to ASCII values representing the flag.

To convert the image to RGB values, one could simple search PNG to RGB and find this website. Opening the output file in a hex editor or simply running cat on the it would produce the flag.

However, the real technical term for a similar file is a bitmap (.BMP). An uncompressed bitmap file represents its bits in RGB but in 3 byte little endian (BGR instead of RGB) which may make it harder to read. Nonetheless, using a hex editor, one can decode the flag after converting from PNG to BMP as well.

vogcetc-h{gsm3myr03R_rGdn33ulB}z3

Yet another alternative, if you are more familiar with tools, is to use zsteg which is able to produce different steganographic outputs, including lowest significant bit (LSB) and RGB bytes.

$ zsteg -a image.png

b8,r,lsb,xy .. text: "gthsm0_d3B3"

b8,g,lsb,xy .. text: "oe-g3rRG3lz"

b8,b,lsb,xy .. text: "vcc{my3rnu}"

b8,rgb,lsb,xy .. text: "govtech-csg{m3m0ry_R3dGr33nBlu3z}"

b8,bgr,lsb,xy .. text: "vogcetc-h{gsm3myr03R_rGdn33ulB}z3"

b8,rgb,lsb,xy,prime .. text: "h-csg{0rydGr"

b8,bgr,lsb,xy,prime .. text: "c-h{gsyr0rGd"

b8,r,lsb,XY .. text: "3B3d_0mshtg"

b8,g,lsb,XY .. text: "zl3GRr3g-eo"

b8,b,lsb,XY .. text: "}unr3ym{ccv"

b8,rgb,lsb,XY .. text: "3z}Blu33ndGr_R30rym3msg{h-ctecgov"

b8,bgr,lsb,XY .. text: "}z3ulBn33rGd3R_yr0m3m{gsc-hcetvog"

b8,rgb,lsb,XY,prime .. text: "3z}m3mh-c"

b8,bgr,lsb,XY,prime .. text: "}z3m3mc-h"

Flag: govtech-csg{m3m0ry_R3dGr33nBlu3z}

Voices in the head

Points: 1692

Solves: 26

Challenge Description

We found a voice recording in one of the forensic images but we have no clue what’s the voice recording about. Are you able to help?

Initial Analysis

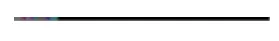

We are given a WAV audio file. With our limited knowledge of WAV stegnography, we had to rely on previous CTF experience. First we analyze the spectrogram. Using Audacity, the spectrogram of the WAV file can be viewed. To open the spectrogram in Audacity, click the dropdown arrow on the left panel beside the file name.

aHR0cHM6Ly9wYXN0ZWJpbi5jb20vakVUajJ1VWI=

The text found is a base64 text as seen from the variation of letters used and the = padding to ensure the length is a multiple of 4. After decoding it (using https://base64decode.org or base64 tool), we find a pastebin link (https://pastebin.com/jETj2uUb) which contains the text below.

++++++++++[>+>+++>+++++++>++++++++++<<<<-]>>>>++++++++++++++++.------------.+.++++++++++.----------.++++++++++.-----.+.+++++..------------.---.+.++++++.-----------.++++++.

This is code written in the brainf*ck programming language, notorious for its minimalism. Running this code on an online compiler yields the text thisisnottheflag. Welp, looks like a dead end.

Back to the WAV file

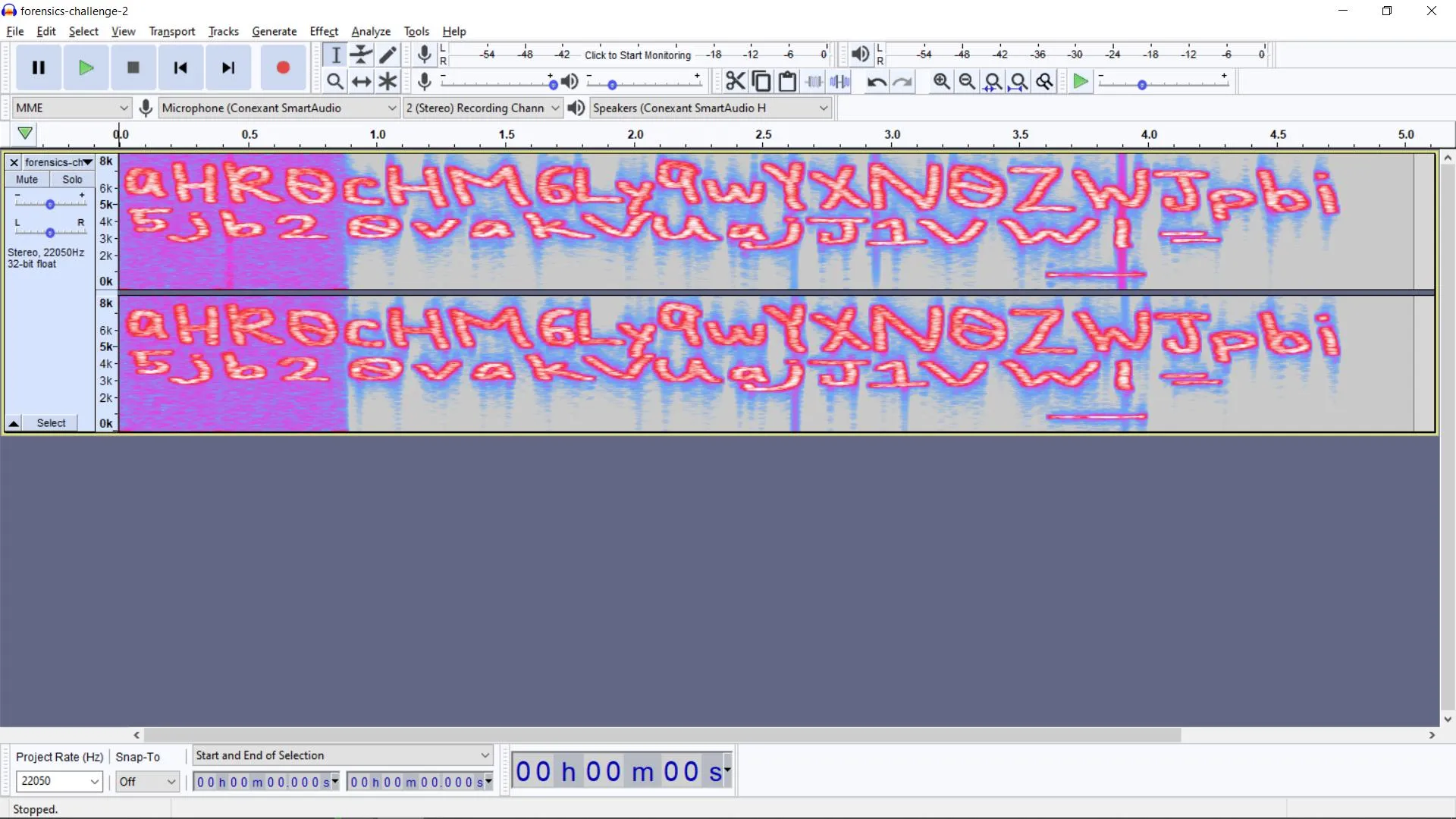

After awhile, due to the challenge title not being sufficiently clear, the following hint was given: Xiao wants to help. Will you let him help you?. Xiao is a reference to Xiao Steganography. Steganography is a method used for hiding information in files, in this case, WAV files. Using a Xiao Steganography decoder, we notice that there is a ZIP file hidden in the WAV file.

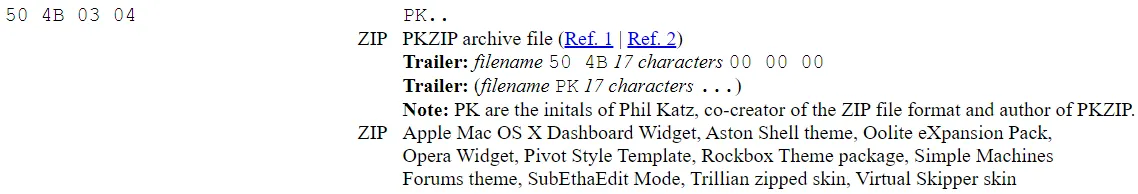

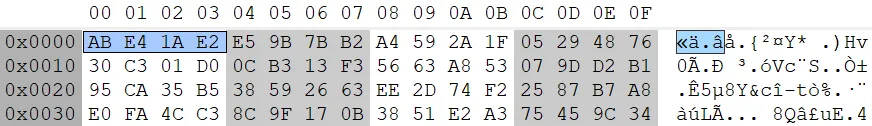

Upon attempting to extract the files, we realize that the ZIP file is invalid. When viewed in a hex editor, the file signature is incorrect as it does not correspond to a ZIP file as seen from this website. For those new to CTFs, all files contain a file signature - a fixed pattern of bytes to begin the file, sometimes called magic bytes.

Edit: At the point of writing, the Gary Kessler website may have been taken down. You can still access the archived website.

Hence, I suspected that the file was encrypted using the Xiao Steganography password field. But what could the password be?

The only string we’ve got is thisisnottheflag from the brainf*ck code. When this was input into the password field and the ZIP file was extracted, we could finally obtain a valid ZIP file

Extracting the ZIP contents

While attempting to extract the ZIP, a password was requested. Since trying the same password (thisisnottheflag) doesn’t work, looks like we don’t have a password this time. What if the password was stored in plaintext, such as in a comment, in the ZIP? Running strings would return the following:

$ strings xiao.zip

.

.

.

This is it.docx

govtech-csg{Th1sisn0ty3tthefl@g}PK

Similar to the previous string, since they tell you that that text is NOT the flag, it’s most likely the password for the ZIP. Lo and behold, using govtech-csg{Th1sisn0ty3tthefl@g} as the password extracts all the contents of the ZIP. After opening the docx file inside, we obtain the flag!

Flag: govtech-csg{3uph0n1ou5_@ud10_ch@ll3ng3}

Internet of Things

COVID’s Communication Technology!

Points: 984

Solves: 10

Challenge Description

We heard a rumor that COVID was leveraging that smart city’s ‘light’ technology for communication. Find out in detail on the technology and what is being transmitted.

Initial Analysis

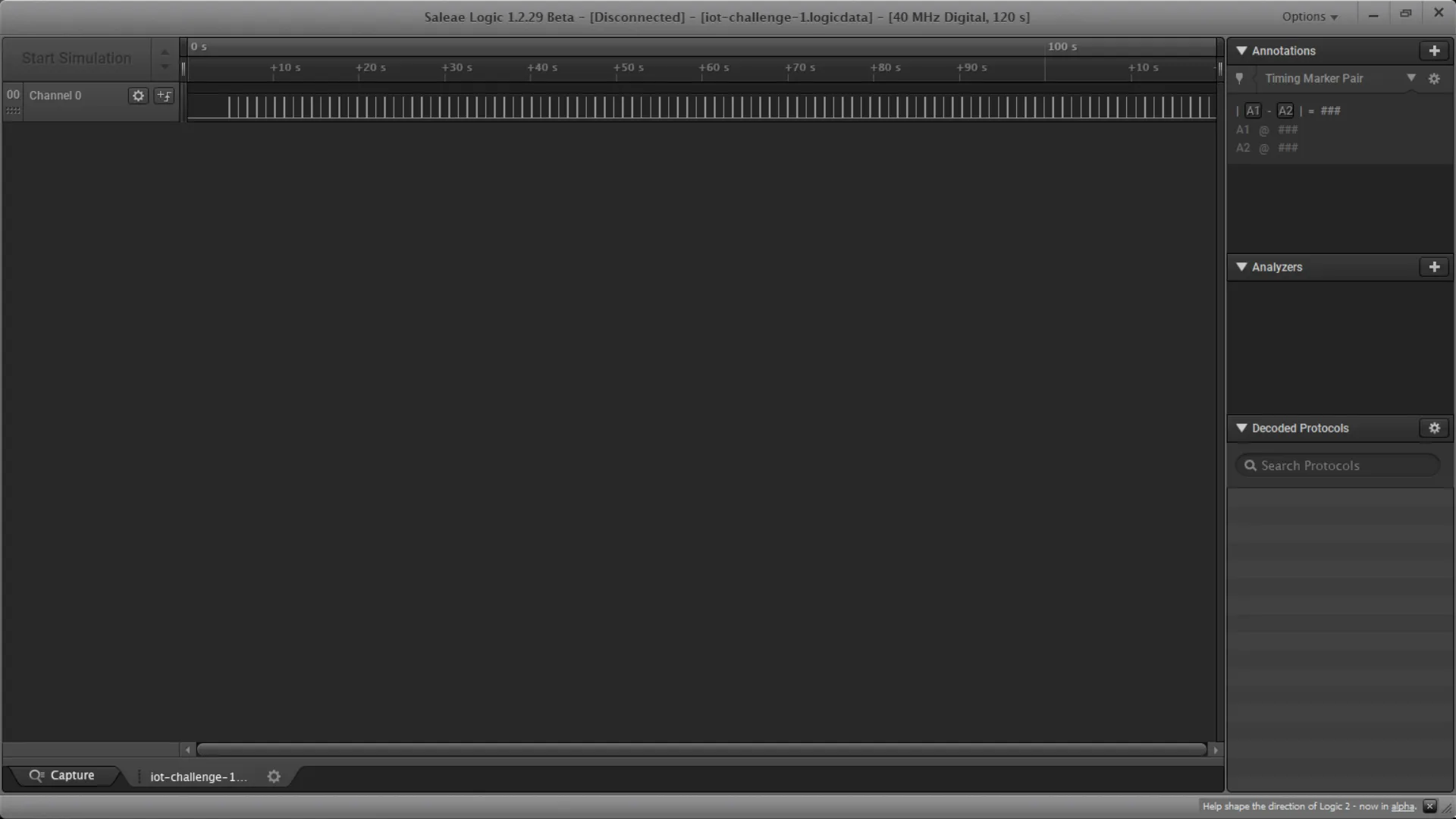

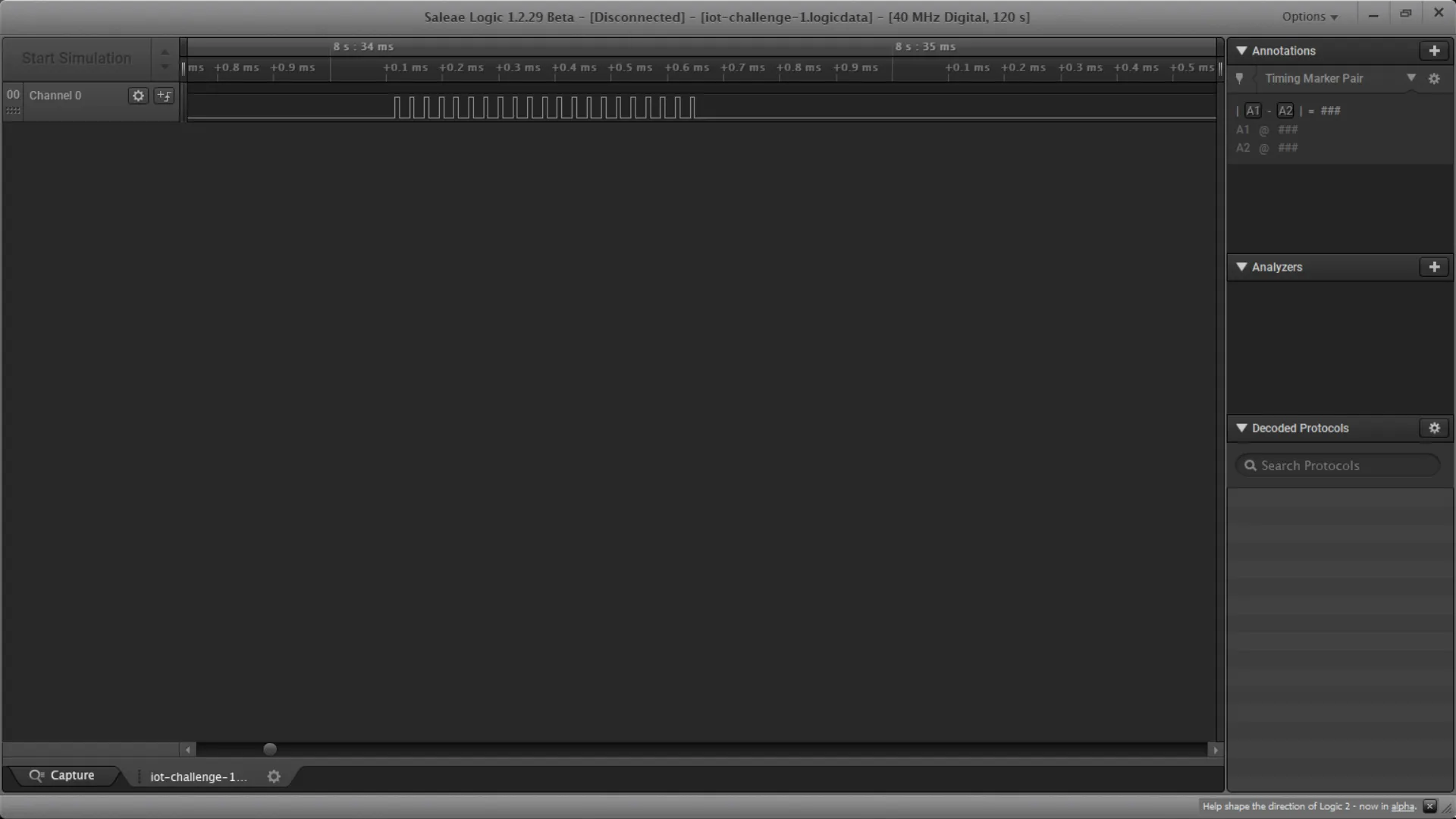

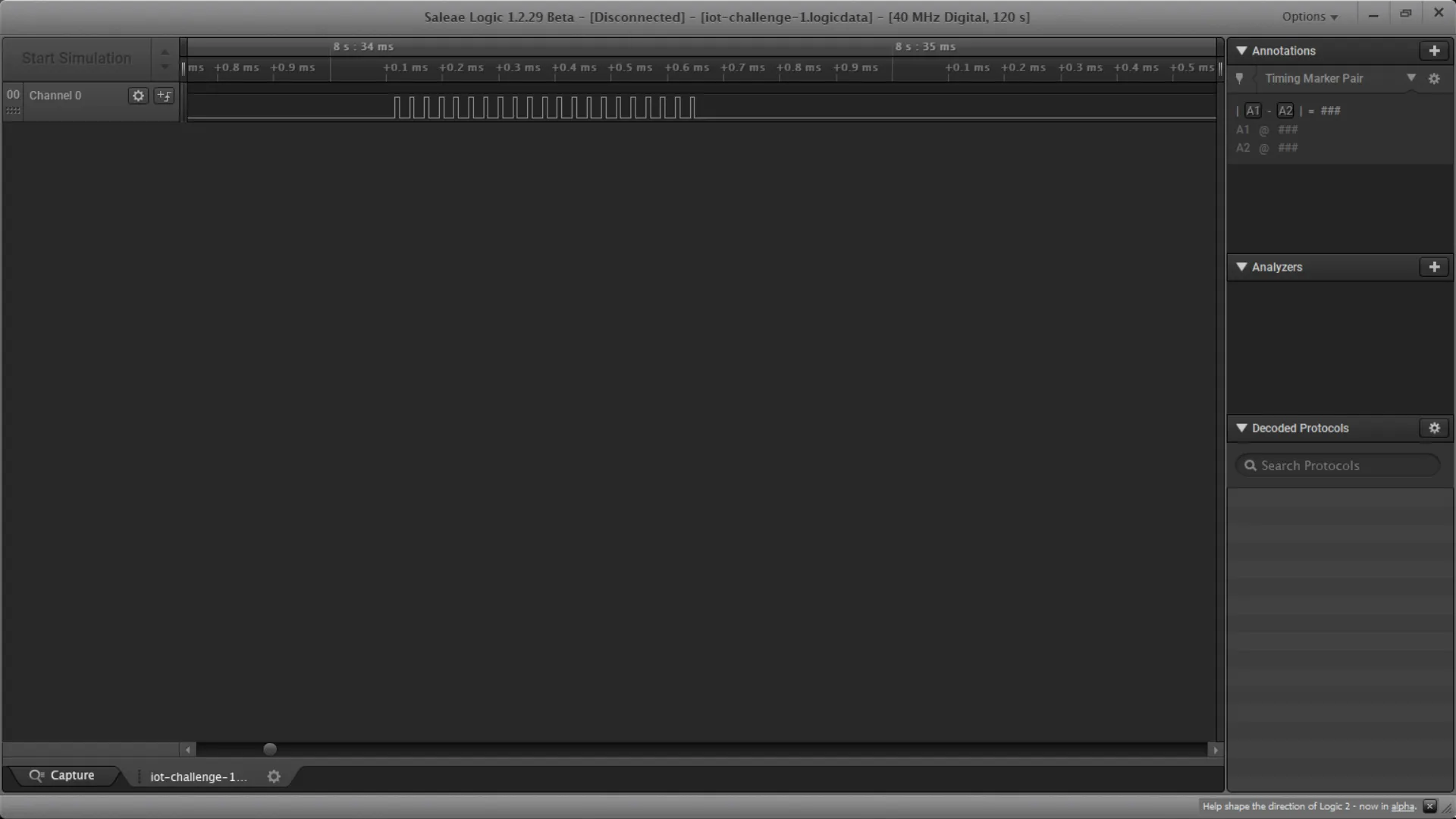

We are given a .logicdata file. After some research, we find that it is a capture output from a Saleae logic analyzer. Essentially, the deivce logs the output of digital/analog pins.

From the challenge description, we know that it is a communication between 2 devices.

Opening the file in the Saleae Logic Analyzer software (hence forth referred to as Saleae), we find that only a single channel/wire is used to transmit data. Note: for .logicdata files, only Saleae version 1 can be used.

About Communication Protocols

If you are only concerned with the solution and already have some basic knowledge of hardware protocols, feel free to skip this section.

Since this challenge is in the IoT category, I figured I should provide a brief background about communication protocols. In order for 2 devices to send data to each other, a protocol has to be established, similar to typical network transmission protocols, but at a hardware level. Usually, the data line is digital (0 or 1). This is true for this challenge as the data being sent is “light communication”.

Examples of common protocols are Serial UART and I2C (pronounced I-squared-C). You can read up on them on your own. But most of them have a pretty standard format: header, address (if more than 2 devices), message length, message. This forms the basis of my initial solution.

Coming from a robotics background, I am familiar with hardware protocols, even coding one based off the I2C protocol recently. I will discuss 2 key ideas that are seen in many protocols: Clocks and packet structures.

In every data transmission, in order to differentiate multiple consecutive bits of the same value (e.g. 1111) a clock is usually established. In systems with more than 1 wire, the clock line (SCL in I2C or CLK) alternates between 0 and 1. Since the system given uses 1 wire, there must be a fixed clock rate, making it easier to read our data as we do not have to worry about rising and falling edges on our clock line.

There is also typically a fixed packet structure. In I2C, it is <packet header><address><length><data>

- The header can simply be a HIGH signal to start the data transmission

- Addresses are used in systems with multiple devices

- Length is the string length of the data. Alternatively, some systems may prefer a fixed packet length or a terminator (fixed string to determine end of sequence)

My Initial Solution

If you are uninterested in my failed almost unimportant attempts, skip this section. However, note that skipping this section also assumes you have used the Saleae software before or can figure it out on your own.

Of course, the easiest way to start this challenge is to try all the different analyzers (right panel). That didn’t work. So I proceeded to analyze the data packets manually.

As seen below, each packet begins with a long HIGH, a long LOW, followed by a sequence of HIGHs and LOWs of fixed width (clock timing has been established). It is interesting to note how a HIGH also has LOWs beside it which does not occur in many protocols.

Scrolling in on each HIGH reveals that it is an oscillating signal, making it even harder for certain analyzers to read.

Thus, I decided to write a python script to parse the data. The data can be exported to via options > Export data. I assumed the following to be the headers (including addresses): <long HIGH><long LOW>1111111110101010101010101. Anything after would form the data. I then interpreted the data. For the above image, it would’ve been 101011101010110111. I also assumed a fixed packet length, padding each packet to a multiple of 8 bits. However, converting this to ASCII didn’t work, even if I used a 7-bit ASCII instead.

It was at this point I realized my approach was probably wrong. The challenge must be telling something else.

The Real Solution

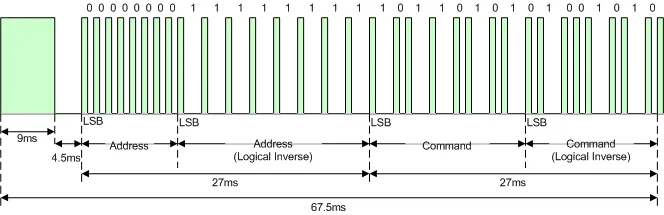

It dawned upon me that light protocol could refer to an infrared light protocol (NEC IR). I googled about the NEC IR protocol and out came this image.

Bingo! This looks EXACTLY like what we are given!

In each NEC IR packet, the value of each bit is determined by the time between 2 HIGHs. A long 9ms HIGH and 4.5ms LOW signals the start. Followed by the address and its logical inverse, and then the data and its logical inverse for verification.

The Saleae Logic Analyzer software does not officially support the NEC IR protocol so if I wanted to use the software’s analyzer, I would’ve had to download the Saleae SDK and import a library. I also figured that since each “HIGH” contains multiple oscillations of HIGHs and LOWs, this may introduce errors. Instead, we can export the data to a CSV and use a Python script to decode the data whilst ignoring the “noise”.

In addition, we notice that the last quarter of the data packets given are not an exact logical inverse of the 3rd quarter. This means the data in our capture does not exactly correspond to the original NEC IR specifications. So perhaps using a script to parse this data is simpler than trying to make an existing analyzer work.

Using the Python script below, the bits of the data can be extracted including the headers and addresses. Thresholds for headers and timings between bits could be empirically derived from Saleae in case the transmission does not directly correspond to the original NEC IR specifications.

import pandas as pd

# Empirically determined timings for 0s and 1s

zeroTime=0.0005698

oneTime=0.001725

df = pd.read_csv('raw.csv')

outstr = ''

prevT = 0

prevX = 0

prevOne=0

first = True

threshold = (zeroTime+oneTime)/2

print "Threshold:",threshold

for index, row in df.iterrows():

t = row['t']-prevT

if t > 0.0001: #Ignoring noise where gap between 2 HIGHs less than 0.1ms

if t > 0.5: #If gap between 2 HIGHs is more than 500ms, start next packet (ie next line in output string)

if not first: outstr += '\n'

first = False

else: #When a valid HIGH is detected, determine the value of the bit based on the time between the two

if prevX==0:

outstr+= '1' if t>threshold else '0'

prevT = row['t']

prevX = row['x']

#Save output string to file

with open('out.txt','w') as f:

f.write(outstr)

The output of the above script produces a text file including headers and addresses. The block below only contains one of 6 repeated instances - the message was sent 6.5 times.

100000000111111110000000000000000

100000000111111110000000000000000

100000000111111110110011101101111

100000000111111110111011001110100

100000000111111110110010101100011

100000000111111110110100000101101

100000000111111110110001101110011

100000000111111110110011101111011

100000000111111110100001101010100

100000000111111110110011001011111

100000000111111110100100101010010

100000000111111110101111101001110

100000000111111110100010101000011

100000000111111110101111100110010

100000000111111110011000001000000

100000000111111110011000000100001

100000000111111110101111101111101

Since the address and its logical inverse is consistent throughout (only 1 destination address), the header, address and inverse address can be removed. I used a simple find and replace in a text editor to remove 10000000011111111. The first 2 lines can also be excluded since they are null bytes.

0110011101101111

0111011001110100

0110010101100011

0110100000101101

0110001101110011

0110011101111011

0100001101010100

0110011001011111

0100100101010010

0101111101001110

0100010101000011

0101111100110010

0011000001000000

0011000000100001

0101111101111101

Copying the above text into a binary to ASCII converter, we obtain the flag govtech-csg{CTf_IR_NEC_20@0!_}, except for an extra ‘_’ which could’ve been added to make the string a multiple of 2 characters.

Flag: govtech-csg{CTf_IR_NEC_20@0!}

I smell updates!

Points: 1986

Solves: 5

Challenge Description

Agent 47, we were able to retrieve the enemy’s security log from our QA technician’s file! It has come to our attention that the technology used is a 2.4 GHz wireless transmission protocol. We need your expertise to analyse the traffic and identify the communication between them and uncover some secrets! The fate of the world is on you agent, good luck.

Flag Format:

govtech-csg{derived-value}

Initial Analysis

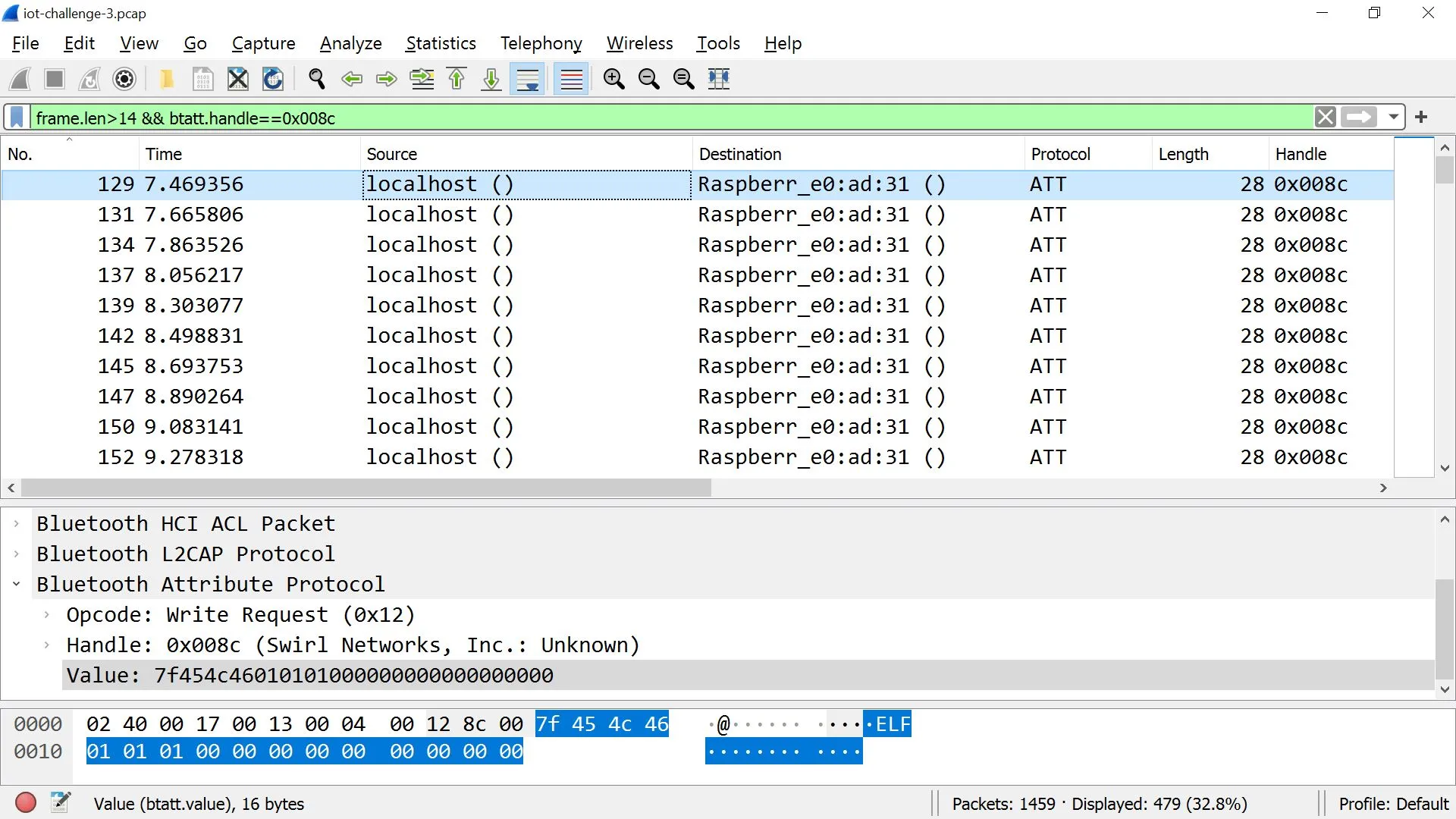

We are provided with a iot-challenge-3.pcap file, which can be analysed using Wireshark. As usual, I use a simple strings command first to check for anything interesting:

Galaxy S7 edge

_tk

Bro: Dude did u ate my chips

/lib/ld-linu

x-armhf.so.3

(Too cool 4 u) TK: Emma owes me $36 for the dinner

|fUa

libc.so

exit

puts

stdin

printf

fgets

strlen

ibc_start_main

Boss: I will not be in the office

_gmon_start__

IBC_2.4

Boss: Can u help me check smth on my com real quick

It seems there is unencrypted data in the given file. We can tell there are two things to be extracted:

- Messages, such as

Bro: Dude did u ate my chips - An

ELF executable, ARM, which can be seen from the presence of common glibc functions andx-armhf.so.3

PCAP Analysis

Keep in mind the focus is to find and extract those data bytes, and filter out all other packets

By opening the pcap file in Wireshark, we see ATT and other protocols. As usual, we turn to Google for unfamiliar stuff.

From this website:

Attribute Protocol (ATT) Bluetooth Low Energy brought two core specifications and every Low Energy profile is supposed to use them. Attribute Protocol and Generic Attribute Profile.

Attribute Protocol is a low-level layer that defines how to transfer data. It identifies the device discovery, reading and writing attributes on a fellow device.

On the other hand, Generic Attribute Profile is built on the top of ATT to give high-level services to the manufacturer implementing LE. These services are basically used to manage the data transfer process in a more systematic way. For example, GATT defines if a device’s role is going to be Server or Client.

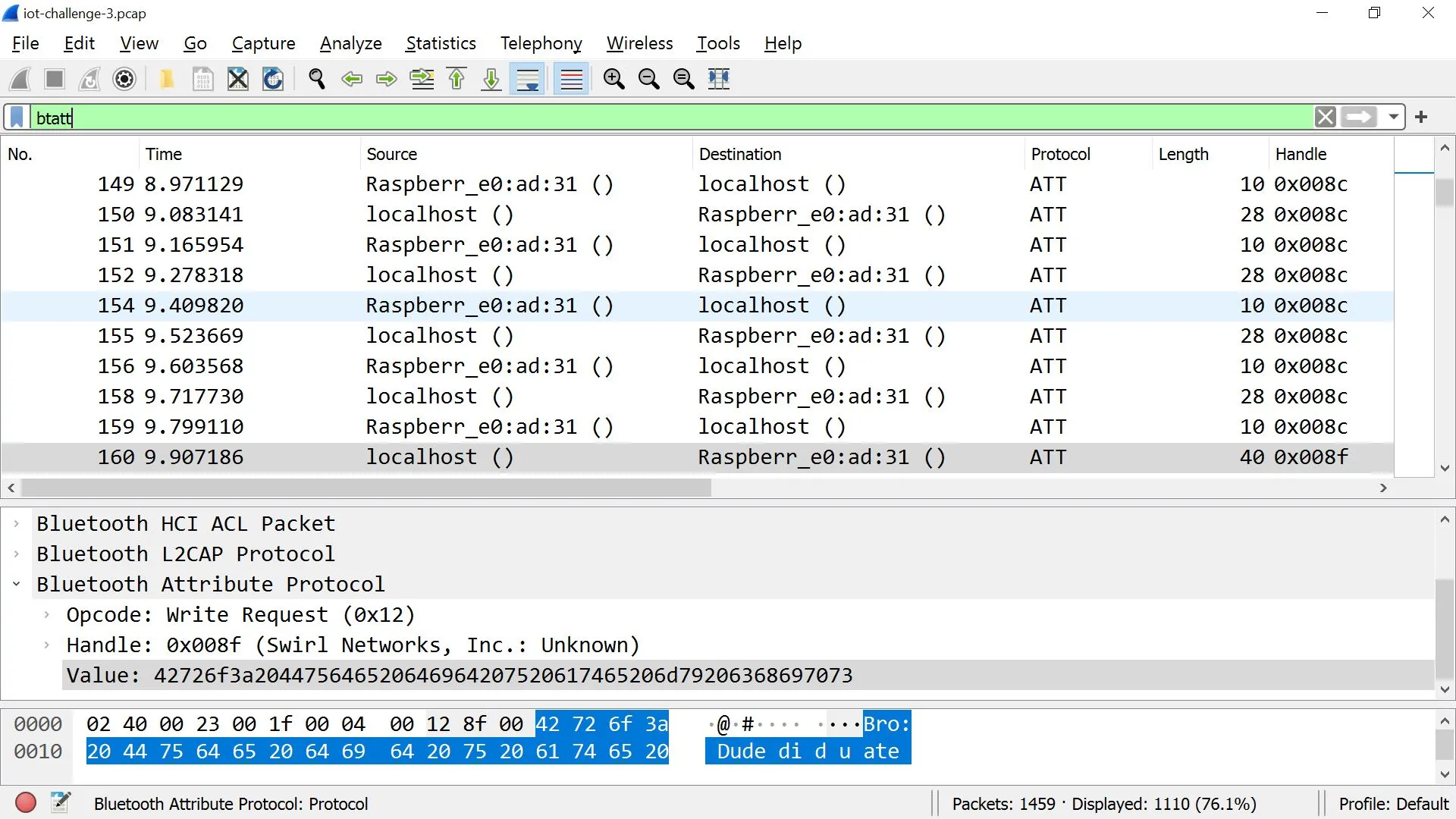

We now know that ATT is used in Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), and used to transfer data. To learn more in-depth about the ATT protocol, check out this this post on StackOverflow. As we want to extract data, we filter out the other protocols using btattin the Wireshark display filter:

We notice that data is transfered through the Value field in packets. Also, by scrolling through the packets, we notice only two specific Handle values contain relevant data:

-

Handle 0x008fcontains text messages -

Handle 0x008ccontains bytes of anELF executable

Packets with these two Handle values, can be filtered using these display filters:

btatt.handle==0x008fbtatt.handle==0x008c

Also, only packets with a length above 14 contain data. Hence, we add the following to our display filter:

frame.len>14

By combining the two, we view only relevant packets with data, such as:

btatt.handle==0x008c && frame.len>14

Note: Check out Wireshark’s display filter expressions if unfamilar

Extracting data bytes

Now that we know how to filter the relevant packets, we need to extract the data bytes from these packets. This can be done using tshark. Using tshark -h, we find these relevant options:

| Option and Format | Explanation |

|---|---|

-r <infile>, --read-file <infile> |

set the filename to read from (or ‘-‘ for stdin) |

-Y <display filter>, --display-filter <display filter> |

packet display filter in Wireshark display filter |

-T pdml | ps | psml | json | jsonraw | ek | tabs | text | fields |

format of text output |

-e <field> |

field to print if -Tfields selected (e.g. tcp.port) |

Thus, data can be extracted using the command:

tshark -r iot-challenge-3.pcap -T -Y "frame.len>14 && btatt.handle==0x008f" -e "btatt.value"

The output from tshark can be piped into a file using the > operator. I used the following python code to convert the data bytes into their corresponding files:

# To parse messages

raw_data = open('messages_raw', 'r')

lines = raw_data.readlines()

messages = []

for line in lines:

message = line[:-1].decode('hex')

messages.append(message + '\n')

message_file = open('messages.txt', 'w')

message_file.writelines(messages)

# To parse data into ELF

import binascii

raw_data = open('data', 'r')

lines = raw_data.readlines()

elf = open('elf_file', 'wb')

messages = []

for line in lines:

byte_string = binascii.unhexlify(line[:-1])

elf.write(byte_string)

We end up with the following messages, which do not seem to be important:

Bro: Dude did u ate my chips

(Too cool 4 u) TK: Emma owes me $36 for the dinner

Boss: I will not be in the office

Boss: Can u help me check smth on my com real quick

Boss: Check my calendar for today

Boss: It's on my desk

(Too cool 4 u) Emma: $36??

(Too cool 4 u) TK: Well $26 for the steak $10 for the drinks

(Too cool 4 u): Max: Cool..

Boss: Any updates?

Boss: Zzzzz

Boss: What is taking so long?!

(Too cool 4 u) Brad: Last night was LITTTT

Mom: I made dinner

Boss: U got to be kidding me

Boss: Password I gave is right

(Too cool 4 u) Meg: Thanks for the dinner outing!

Boss: Do u even know how to use a com??!

John: He's onto you again huh?

Tammy: U free tonight?

(Too cool 4 u) Don: Dinner anyone?

Tammy: Urgent text me ASAP

Boss: WELL??

(Too cool 4 u) Brad: Sure where to?

(Too cool 4 u) Brad: PM me

We also end up with the following executable, which can be identified using file <ELF_FILE>:

ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld-linux-armhf.so.3, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=d73f4011dd87812b66a3128e7f0cd1dcd813f543, not stripped

Reversing: Static Analysis

Using a decompiler, such as Ghidra or IDA, we can see the program logic. Below is a cleaned-up version of the decompilation:

int main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp) {

printf("Secret?");

fgets(&buf, 10, stdin);

if ( strlen(&buf) != 8 ) {

puts("Sorry wrong secret! An alert has been sent!");

exit(0);

}

i = 0;

buf_len = strlen(&buf);

if ( buf[0] == magic(105 - buf_len) ) ++i;

if ( buf[1] == magic(105 ^ 0x27) ) ++i;

if ( buf[2] == magic(105 + 11) ) ++i;

if ( buf[3] == magic(2 * buf[1] - 51) ) ++i;

if ( buf[4] == magic(0x42) ) ++i;

if ( buf[5] == magic((8 * (i - 1)) | 1) ) ++i;

temp = buf[3] + buf[4] + buf[5];

c = (temp ^ (buf[3] + buf[5] + 66)) + 101;

if ( buf[6] == magic(c) ) ++i;

if ( i == 7 )

puts("Authorised!");

else

puts("Sorry wrong secret! An alert has been sent!");

}

We see that the program takes in input of 10 bytes using fgets():

fgets(&buf, 10, stdin);

The program checks if the length of the input is 8 bytes long, and terminates with a wrong message if it isn’t: Note: The correct input actually has a length of 7 as fgets() appends a \n character to the end of input

if ( strlen(&buf) != 8 ) {

puts("Sorry wrong secret! An alert has been sent!");

exit(0);

}

The program then compares each byte to a value generated using a magic() function, and increments i by 1 if true.

i=0;

buf_len = strlen(&buf);

if ( buf[0] == magic(105 - buf_len) ) ++i;

if ( buf[1] == magic(105 ^ 0x27) ) ++i;

if ( buf[2] == magic(105 + 11) ) ++i;

if ( buf[3] == magic(2 * buf[1] - 51) ) ++i;

if ( buf[4] == magic(0x42) ) ++i;

if ( buf[5] == magic((8 * (i - 1)) | 1) ) ++i;

temp = buf[3] + buf[4] + buf[5];

c = (temp ^ (buf[3] + buf[5] + 66)) + 101;

if ( buf[6] == magic(c) ) ++i;

At the end, it checks if i equals 7, and prints a success or fail message accordingly:

if ( i == 7 )

puts("Authorised!");

else

puts("Sorry wrong secret! An alert has been sent!");

It would be possible to obtain the flag purely by static analysis of the magic() function. However:

-

magic()actually contains four other nested functions, making it tedious to reverse. - I am lazy.

Thus, we move on to dynamic analysis.

Reversing: Dynamic Analysis

Setup

To setup Linux to run arm binaries, check out this post.

To perform dynamic analysis, we will debug the binary with gdb. To setup:

- Install gdb-multiarch with

sudo apt-get install gdb-multiarch - In one terminal window, run the binary with

qemu-arm -g <PORT> ./<ELF_FILE>. For example:qemu-arm -g 1234 ./elf_file - In another terminal window, run:

gdb-multiarch <ELF_FILE>-

target remote HOST:PORT, for example:target remote localhost:1234 -

c, to continue execution of the program

This allows us to run the binary normally, and pause execution in gdb using <ctrl-c> to debug.

Obtaining the flag

As mentioned before, the binary compares each byte to a value returned by magic(). We notice that:

- The bytes are checked from index 0 to 6

- Following bytes do not affect the check of previous bytes. This means, that

buf[6]will not affect the value returned bymagic()when checkingbuf[3], or any other previous bytes.

This means we can obtain the correct character at any position if we know the correct characters in previous positions. As such, we do the following:

- Set a breakpoint in

magic()to find its return value - Run the binary until breakpoint is hit

- Print the return value of

magic() - Append this value to the input

- Repeat until we get the entire password

Before diving into gdb, remember that the aim is to obtain the return values of magic()

We use the disas command to obtain the disassembly of the magic() function:

(gdb) disas magic

Dump of assembler code for function magic:

0x000107c8 <+0>: push {r11, lr}

0x000107cc <+4>: add r11, sp, #4

0x000107d0 <+8>: sub sp, sp, #8

0x000107d4 <+12>: mov r3, r0

0x000107d8 <+16>: strb r3, [r11, #-5]

0x000107dc <+20>: ldrb r3, [r11, #-5]

0x000107e0 <+24>: mov r0, r3

0x000107e4 <+28>: bl 0x10820 <magic2>

0x000107e8 <+32>: mov r3, r0

0x000107ec <+36>: strb r3, [r11, #-5]

0x000107f0 <+40>: mov r0, #3

0x000107f4 <+44>: mov r1, #2

0x000107f8 <+48>: bl 0x10980 <min>

0x000107fc <+52>: mov r3, r0

0x00010800 <+56>: uxtb r2, r3

0x00010804 <+60>: ldrb r3, [r11, #-5]

0x00010808 <+64>: add r3, r2, r3

0x0001080c <+68>: strb r3, [r11, #-5]

0x00010810 <+72>: ldrb r3, [r11, #-5]

0x00010814 <+76>: mov r0, r3

0x00010818 <+80>: sub sp, r11, #4

0x0001081c <+84>: pop {r11, pc}

End of assembler dump.

In x86 ARM architecture, return values are stored in registers (r0 in this case). We set a breakpoint right before magic() ends, with the following:

(gdb) b *magic+84

Breakpoint 1 at 0x1081c

As we want to print the value stored in r0 as a character everytime the breakpoint is hit, we can use the define hook-stop command:

(gdb) define hook-stop

Type commands for definition of "hook-stop".

End with a line saying just "end".

>print (char) $r0

>end

We then continue execution three times until the character printed is no longer correct.

(gdb) c

Continuing.

$8 = 97 'a'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb) c

Continuing.

$9 = 78 'N'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb) c

Continuing.

$10 = 116 't'

(gdb) c

Continuing.

$11 = 143 '\217'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

This is because the return value of magic() now depends on previous characters, as seen in this code:

if ( buf[3] == magic(2 * buf[1] - 51) ) ++i;

Thus, we restart execution and enter aNtaaaa as input:

In gdb terminal window

(gdb) kill

Kill the program being debugged? (y or n) y

[Inferior 1 (process 1) killed]

(gdb) target remote localhost:1234

Remote debugging using localhost:1234

(gdb) c

In other terminal window

$ qemu-arm -g 1234 ./elf_file

Secret?aNtaaaa

This allows us to obtain more correct characters in gdb:

(gdb) c

Continuing.

$13 = 97 'a'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb) c

Continuing.

$14 = 78 'N'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

$15 = 116 't'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

$16 = 105 'i'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

$17 = 66 'B'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

$18 = 17 '\021'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

We repeat the process, which gives us the entire flag before the program terminates:

(gdb) c

Continuing.

$21 = 97 'a'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb) c

Continuing.

$22 = 78 'N'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

$23 = 116 't'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

$24 = 105 'i'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

$25 = 66 'B'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

$26 = 33 '!'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

$27 = 101 'e'

Breakpoint 1, 0x0001081c in magic ()

(gdb)

Continuing.

[Inferior 1 (process 1) exited normally]

Error while running hook_stop:

No registers

The above shows us the secret pass is aNtiB!e. Let us check:

$ qemu-arm elf_file

Secret?aNtiB!e

Authorised!

It is correct, hence the flag is govtech-csg{aNtiB!e}

Flag: govtech-csg{aNtiB!e}

Mobile

A to Z of COViD!

Points: 1986

Solves: 5

Challenge Description

Over here, members learn all about COViD, and COViD wants to enlighten everyone about the organisation. Go on, read them all!

Flag Format:

govtech-csg{alphanumeric-and-special-characters-string

Initial Analysis

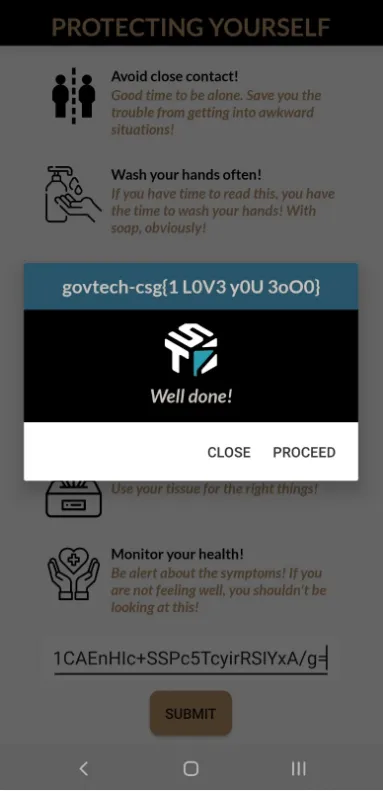

This challenge to the activity launched by CovidInfoActivity.java. Launching the activity in an emulator, the following screen is displayed:

The text field asks for the flag, and upon submission, displays a toast showing Flag is wrong!. We now know the flag entered is most probably checked in the onClick() function of the submit button.

Using JADX, we can obtain the decompiled Java source code of the apk. As mentioned above, we look for the onClick() function in CovidInfoActivity.java:

public void onClick(View v) {

if (this.f2970b.encryptOrNull(((EditText) CovidInfoActivity.this.findViewById(R.id.editText_enteredFlag)).getText().toString()).replaceAll("\\n", BuildConfig.FLAVOR).equalsIgnoreCase(CovidInfoActivity.this.f2969b)) {

c.a builder = new c.a(CovidInfoActivity.this);

View view = LayoutInflater.from(CovidInfoActivity.this).inflate(R.layout.custom_alert, (ViewGroup) null);

((TextView) view.findViewById(R.id.title)).setText("Congrats!");

((TextView) view.findViewById(R.id.alert_detail)).setText("Well done!");

f.a.a.a.a.e.b.a().d(true);

builder.h("Proceed", new DialogInterface$OnClickListenerC0073a());

builder.f("Close", new b());

builder.k(view);

builder.l();

Toast.makeText(CovidInfoActivity.this.getApplicationContext(), "Flag is correct!", 0).show();

return;

}

Toast.makeText(CovidInfoActivity.this.getApplicationContext(), "Flag is wrong!", 0).show();

}

Our entered flag is retrieved by the activity using:

CovidInfoActivity.this.findViewById(R.id.editText_enteredFlag)).getText().toString()

It is then encrypted using a function named encryptOrNull(), before being compared to CovidInfoActivity.this.f2969b. By looking at the code in the same file, we see the following relevant code:

public String f2969b = "jeldexs+ktquD8iQ1CAEnHIc+SSPc5TcyirRSIYxA/g=";

import se.simbio.encryption.Encryption;

public final Encryption f2970b;

public a(Encryption encryption) {

this.f2970b = encryption;

}

CovidInfoActivity.this.f2969b refers to the flag after it is encrypted using encryptOrNull(). We also see that encryptOrNull() is a function imported from Encryption.java, another Java file in the apk. Thus, we take a closer look at that file:

public String encryptOrNull(String data) {

try {

return encrypt(data);

} catch (Exception e2) {

e2.printStackTrace();

return null;

}

}

The encryptOrNull() function calls another function encrypt(), which calls more functions and so on… Manually reversing the code through static analysis seems too tedious, thus we look for another method. Scrolling through Encryption.java, we see there is a function named decryptOrNull():

public String decryptOrNull(String data) {

try {

return decrypt(data);

} catch (Exception e2) {

e2.printStackTrace();

return null;

}

}

Seeing that it is similar to encryptOrNull(), it is same to assume this function decrypts data passed into it. As we have the encrypted flag, we just need to find a way to pass it into decryptOrNull() and obtain the output.

Patching the APK

As mentioned above, we want to call decryptOrNull() on the encrypted flag to get the flag. This would be possible with Frida, however, I chose to patch the apk as that was more familiar to me.

To obtain the smali code of the apk, we use ApkTool:

apktool -r d mobile-challenge.apk -o <OUTPUT_DIR>

As the relevant code in Java is in CovidActivity.java, we look for the smali files related to that. The OnClick() function is found in CovidInfoActivity$a.smali:

.method public onClick(Landroid/view/View;)V

.locals 11

.param p1, "v" # Landroid/view/View;

...

Before diving into patching the code, we identify what we need to do:

- Call

decryptOrNull()on input entered by us - Display the output in the apk

Fortunately, smali code is similar to assembly, making it easier for me to identify the code parts I needed to patch.

Smali Code Analysis

By analyzing the smali code, we see that encryptOrNull() is called on our input, and the encrypted input is stored in the variable v2:

.line 48

.local v1, "enteredFlagString":Ljava/lang/String;

iget-object v2, p0, Lsg/gov/tech/ctf/mobile/Info/CovidInfoActivity$a;->b:Lse/simbio/encryption/Encryption;

invoke-virtual {v2, v1}, Lse/simbio/encryption/Encryption;->encryptOrNull(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/String;

move-result-object v2

The encrypted flag is then fetched and stored in v3, and compared to our encrypted input in v2. The code then jumps to :cond_0 if they are not equal:

.line 51

iget-object v3, p0, Lsg/gov/tech/ctf/mobile/Info/CovidInfoActivity$a;->c:Lsg/gov/tech/ctf/mobile/Info/CovidInfoActivity;

iget-object v3, v3, Lsg/gov/tech/ctf/mobile/Info/CovidInfoActivity;->b:Ljava/lang/String;

invoke-virtual {v2, v3}, Ljava/lang/String;->equalsIgnoreCase(Ljava/lang/String;)Z

move-result v3

const/4 v4, 0x0

if-eqz v3, :cond_0

We see that :cond_0 displays Flag is wrong! in a toast, hence we do not want to jump to :cond_0:

.line 86

:cond_0

iget-object v3, p0, Lsg/gov/tech/ctf/mobile/Info/CovidInfoActivity$a;->c:Lsg/gov/tech/ctf/mobile/Info/CovidInfoActivity;

invoke-virtual {v3}, Landroid/app/Activity;->getApplicationContext()Landroid/content/Context;

move-result-object v3

const-string v5, "Flag is wrong!"

invoke-static {v3, v5, v4}, Landroid/widget/Toast;->makeText(Landroid/content/Context;Ljava/lang/CharSequence;I)Landroid/widget/Toast;

move-result-object v3

invoke-virtual {v3}, Landroid/widget/Toast;->show()V

Should the code not jump to :cond_0, it displays a Congratulations message:

.line 57

.local v7, "details":Landroid/widget/TextView;

const-string v8, "Congrats!"

invoke-virtual {v6, v8}, Landroid/widget/TextView;->setText(Ljava/lang/CharSequence;)V

A more in-depth explanation:

-

equalsIgnoreCaseis similar tocmpassembly. It returns true (1) if both strings are equal, else it returns false (0). The result is then stored inv3 -

if-eqz, similar tojzin assembly, jumps tocond_0if the value stored inv3is equal to 0. - This allows the app to jump to

cond_0and displayFlag is wrong!when the input entered is not equal to the flag.

Patching Smali Code

With the smali code snippets above, we can actually patch the apk to give us the flag:

- Call

decryptOrNull()instead ofencryptOrNull()on input of theeditText. - Jump to

:cond_0when input is equal to the flag, instead of when the flag is wrong. This would allow us to see the congratulations window when we enter a wrong flag instead of a correct one. - Patch the code to display the output from

decryptOrNull()instead ofCongrats!in the congratulations window.

To call decryptOnNull() instead, we simply change the function call in .line 48 :

# From:

invoke-virtual {v2, v1}, Lse/simbio/encryption/Encryption;->encryptOrNull(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/String;

# Changed to:

invoke-virtual {v2, v1}, Lse/simbio/encryption/Encryption;->decryptOrNull(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/String;

In .line 51, we find the instruction opposite of if-eqz, which is if-nez, and make the change:

# From:

if-eqz v3, :cond_0

# Changed to:

if-nez v3, :cond_0

The return value of decryptOrNull() is stored in v2, while the Congrats! message is stored in v8. We make the appropriate changes to .line 57:

# From:

invoke-virtual {v6, v8}, Landroid/widget/TextView;->setText(Ljava/lang/CharSequence;)V

# Changed to:

invoke-virtual {v6, v2}, Landroid/widget/TextView;->setText(Ljava/lang/CharSequence;)V

Building patched APK

To build the apk from smali code, we use apktool:

apktool b <OUTPUT_DIR>

To sign the apk, we follow the steps in this post:

- Create a key using:

keytool -genkey -v -keystore my-release-key.keystore -alias alias_name -keyalg RSA -keysize 2048 -validity 10000

- Sign the apk with:

jarsigner -verbose -sigalg SHA1withRSA -digestalg SHA1 -keystore my-release-key.keystore mobile-challenge.apk alias_name

Flag

We install the patched APK on an emulator and run it normally. Instead of entering the flag in the Info Page, we key in the encrypted flag:

This displays the congratulations window with the flag:

Flag: govtech-csg{1 L0V3 y0U 3oO0}

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT)

Only time will tell!

Points: 691

Solves: 34

This picture was taken sent to us! It seems like a bomb threat! Are you able to tell where and when this photo was taken? This will help the investigating officers to narrow down their search! All we can tell is that it’s taken during the day!

If you think that it’s 7.24pm in which the photo was taken. Please take the associated 2 hour block. This will be 1900-2100. If you think it is 10.11am, it will be 1000-1200.

Flag Example: govtech-csg{1.401146103.927020_1990:12:30_2000-2200} Flag Format: govtech-csg{lat_long_date[two hour block format]} Use this calculator!

Maximum attempts: 3 (Removed later in competition)

Initial Analysis

We are given a jpg image. We are supposed to find the coordinate location (latitude and longitude), the date, as well as a rough time that the image was taken (using a 2h block).

Common sense tells us to scan the barcode on the image. Using barcode scanning apps on our phone such as the Cognex scanner - which is good for scanning other codes as well - we get the text “25 October 2020”. Great! We’ve got one part of the flag. Just need to convert it to the right form for the challenge. (YYYY:MM:DD as seen from the example given)

2020:10:25

The common tool to use when we analyze this image is exiftool. This can give us metadata about the image such as time and location. However, time is pretty much out of the question as seen from the last modified time being 4 December 2020 close to midnight which was when I downloaded the file.

$ exiftool osint-challenge-6.jpg

ExifTool Version Number : 11.88

File Name : osint-challenge-6.jpg

File Size : 123 kB

File Modification Date/Time : 2020:12:04 23:58:48+08:00

File Access Date/Time : 2020:12:09 00:36:23+08:00

File Inode Change Date/Time : 2020:12:04 23:59:24+08:00

File Permissions : rwxrwxrwx

File Type : JPEG

File Type Extension : jpg

MIME Type : image/jpeg

JFIF Version : 1.01

X Resolution : 96

Y Resolution : 96

Exif Byte Order : Big-endian (Motorola, MM)

Make : COViD

Resolution Unit : inches

Y Cb Cr Positioning : Centered

GPS Latitude Ref : North

GPS Longitude Ref : East

Image Width : 551

Image Height : 736

Encoding Process : Baseline DCT, Huffman coding

Bits Per Sample : 8

Color Components : 3

Y Cb Cr Sub Sampling : YCbCr4:2:0 (2 2)

Image Size : 551x736

Megapixels : 0.406

GPS Latitude : 1 deg 17' 11.93" N

GPS Longitude : 103 deg 50' 48.61" E

GPS Position : 1 deg 17' 11.93" N, 103 deg 50' 48.61" E

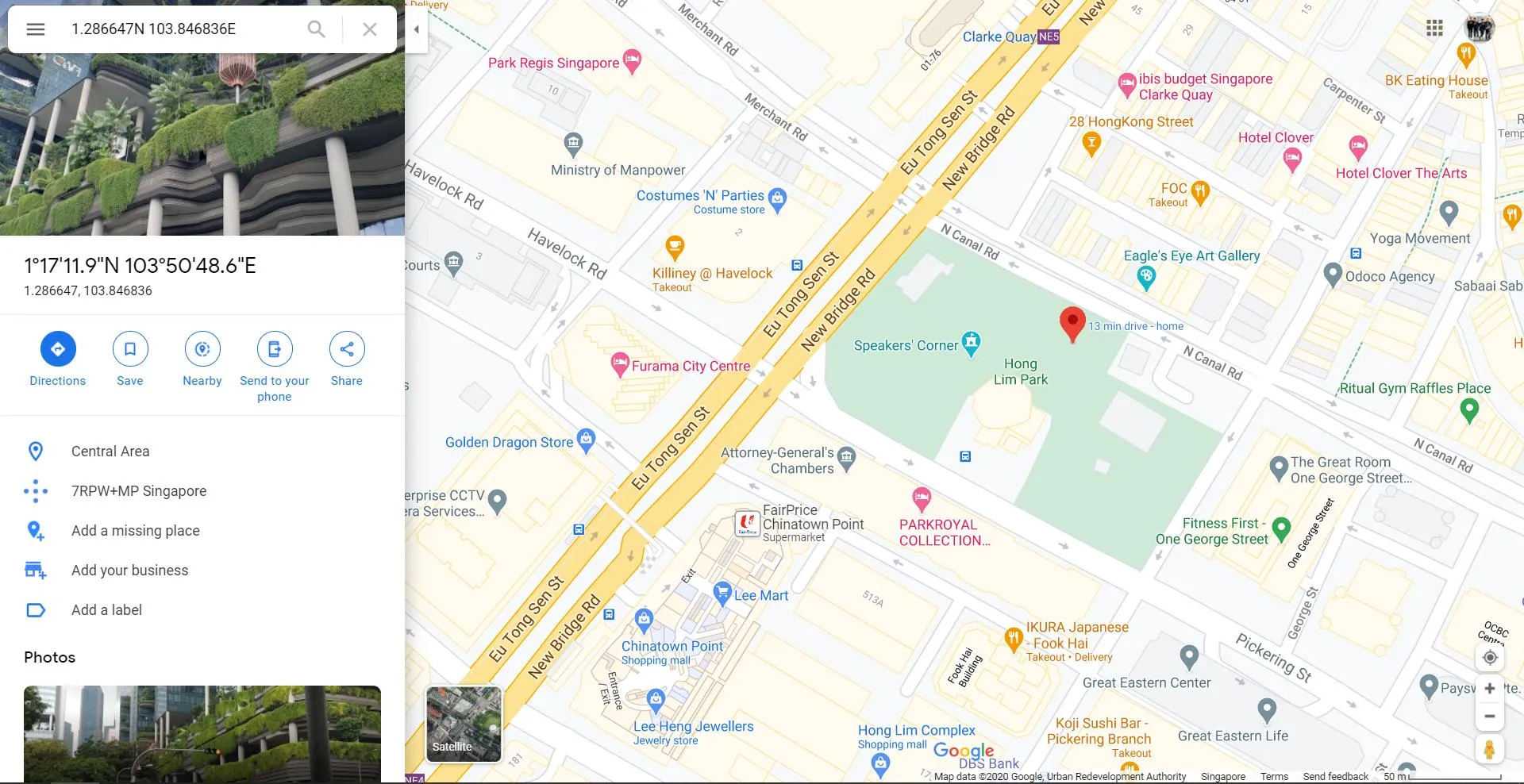

Getting Coordinate Location

At the bottom of the output, we have the GPS latitude and longitude in Degree Minute Seconds (DMS) form. You can convert this form to what the challenge desires (Simply in degrees) on the calculator website given by the challenge. In DMS, the degrees are in whole numbers and the minutes and seconds are used as “decimals”. Placing the latitude and longitude into the calculator, we can get the desired form - Decimal Degrees (DD). There is no need for rounding. The calculator is given by the challenge so we just use whatever precision the calculator gives.

Latitude: 1.286647 Longitude: 103.846836

Finding Time

Now we are left with time. From the image, it looks like the only clue we have for time is the shadow. One method is to use use sun calculations. The second is to use our experience to tell the time. We decided to try the latter as we are convinced that the timing was either from 10-11am or 2-4pm due to the scorching sun. However, we need to find out if the shadow is pointing East or West.

Google Maps shall be our tool of choice. Although this sign points to a familiar place “Speaker’s Corner” in Singapore, the coordinates should be used in order to determine its exact location on a big grassy field.

We can use background buildings in the photo to determine where the photo is facing. In the photo, we see a uniquely shaped (somewhat triangular) building. This is similar to the shapes of the Furama City Center building in Google Maps.

A quick Google search of the building reveals it is the same building. We can further confirm it using street view on the nearby road. We can’t really see the background buildings well, but it sure looks like the UOL building in the photo. Anyways, we can see the Speaker’s Corner sign in the correct orientation, signalling we are on the right track.

Furama City Centre is to the West of the sign. This is because on the web client of Google Maps, North is defaulted to upwards. We thus know that the photographer is facing West. Since the shadow is towards the photographer, it is pointing East, hence, the sun is in the West, concluding the fact that it is in the afternoon.

Our estimates tell us it is somewhere between 2-4pm. This gives us 3 timing answers

1400-1600 1500-1700 1600-1800 (Highly unlikely)

Since we have 3 attempts, we can try the timings until the flag is accepted. This is “smarter” brute forcing. Rather just narrowing it to a 50/50 without the need to learn sun calculations. The correct timing was 1500-1700. This means the photo was taken awhile after 3pm. This is exactly in the middle of what our initial guess was.

1500-1700

Flag: govtech-csg{1.286647_103.846836_2020:10:25_1500-1700}

Sounds of freedom!

Points: 750

Solves: 31

Challenge Description

In a recent raid on a suspected COViD hideout, we found this video in a thumbdrive on-site. We are not sure what this video signifies but we suspect COViD’s henchmen might be surveying a potential target site for a biological bomb. We believe that the attack may happen soon. We need your help to identify the water body in this video! This will be a starting point for us to do an area sweep of the vicinity!

Flag Format: govtech-csg{postal_code}

Initial Analysis

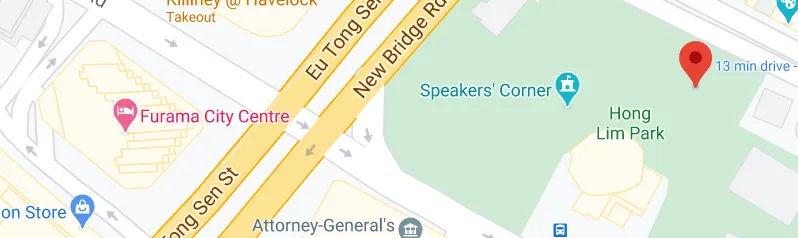

We are given a video and asked to find the location of the waterbody. I have included snapshots of the videos for analysis:

Analysis of Snapshot 1

- Bus Stop alongside the road

- Housing estate has black pillars outside the windows

- Sounds of military aircrafts flying overhead

Analysis of Snapshot 2

- Light blue HDBs on the opposite side

Thought process and Solution

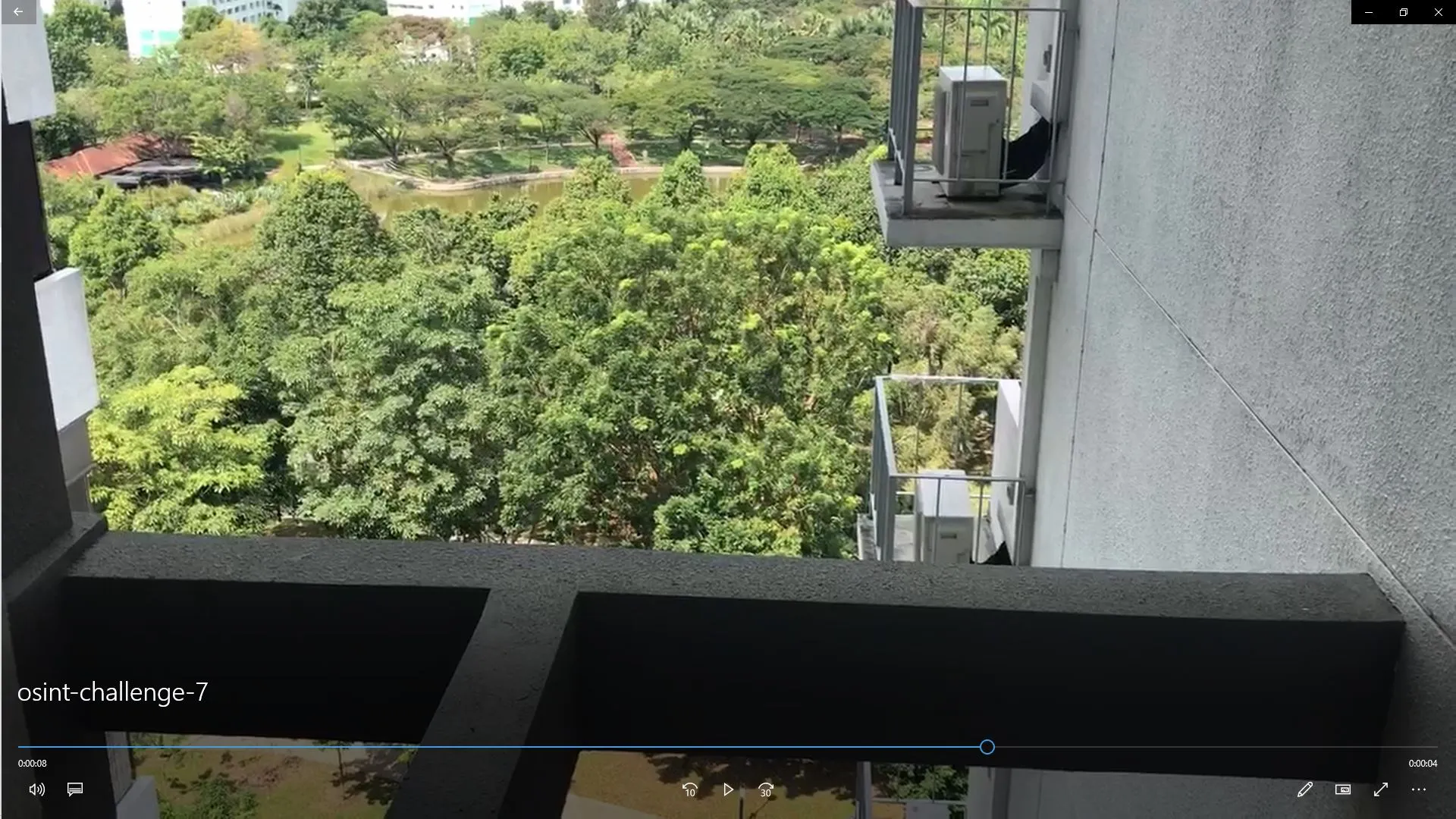

The details from the video should be sufficient to identify the place when we see it on Google Maps. However, looking at all water bodies in Singapore would be too time consuming. Hence, I looked for ways to narrow down possible waterbodies.

The title Sounds of Freedom seems to refer to the miltary aircrafts flying, which led me to think the waterbody was near Paya Lebar Air Base. This immediately narrowed down the search to three locations:

- Punggol Park

- Tampines Quarry

- Bedok Resevoir

We can use Google Street View to look at bus stops near these locations. Keep in mind there should be a housing estate near the bus stop and HDBs opposite the waterbody. Eventually, I found the bus stop shown in the video, located at Punggol Park. A quick search on Google Maps tell us the address is Hougang Ave 10, Singapore 538768.

Flag: govtech-csg{538768}

What is he working on? Some high value project?

Points: 790

Solves: 29

Challenge Description

The lead Smart Nation engineer is missing! He has not responded to our calls for 3 days and is suspected to be kidnapped! Can you find out some of the projects he has been working on? Perhaps this will give us some insights on why he was kidnapped…maybe some high-value projects! This is one of the latest work, maybe it serves as a good starting point to start hunting.

Flag is the repository name!

Developer’s Portal - STACK the Flags

Opening the link provided, there is nothing that stands out at first glance. Since the flag is a repository name, we know we have to find some sort of clue that is related. Perhaps there is something we can find in the page source.

After slowly analyzing the page source, we find a html comment left by the devs.

<a href="https://ctf.tech.gov.sg/">

<h3 style="text-align: center;">Check out STACK the Flags here!</h3>

</a>

<!-- Will fork to our gitlab - @joshhky -->

<p>

<em>

Last updated 04 December 2020

</em>

</p>

</div>

</div>

Hmm… Let’s follow the path and search for @joshhky on gitlab. We can view his profile on gitlab using this link. We can confirm that we are on the right path as we see several projects with “KoroVax” in them, suggesting that this user was indeed created for the purpose of the CTF.

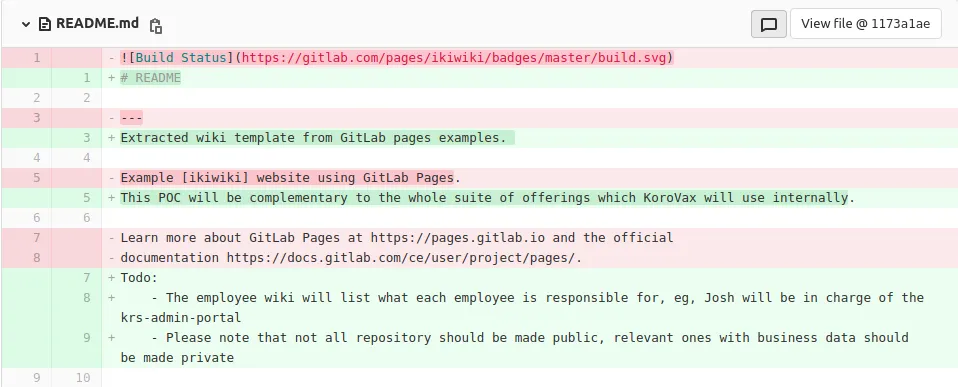

At this stage, we viewed all the repositories and projects he created/imported trying to find any clues. However, majority of them were empty. The only anomaly out of his entire activity was the commit which contained changes in the project README. We can click on the commit ID to view more details about it.

Upon closer inspection, we see that in the Todo, there is a point about how not all repositories should be public. From this, we can guess that the repository that we are searching for is private. However, just above that, there is also another point which notes that Josh (our target) is in charge of krs-admin-portal. This seems suspicious. Perhaps it may be a repository name? No harm trying right?

After wrapping it in the flag format, we try to submit the flag and… it was correct after all :)

Flag: govtech-csg{krs-admin-portal}

Hunt him down!

Points: 970

Solves: 14

Challenge Description

After solving the past two incidents, COViD sent a death threat via email today. Can you help us investigate the origins of the email and identify the suspect that is working for COViD? We will need as much information as possible so that we can perform our arrest!

Example Flag: govtech-csg{JohnLeeHaoHao-123456789-888888} Flag Format: govtech-csg{fullname-phone number[9digits]-residential postal code[6digits]}

Analysing the Email

We are given an eml file. Opening it in a text editor reveals the following.

X-Pm-Origin: internal

X-Pm-Content-Encryption: end-to-end

Subject: YOU ARE WARNED!

From: theOne <theOne@c0v1d.cf>

Date: Fri, 4 Dec 2020 21:27:07 +0800

Mime-Version: 1.0

Content-Type: multipart/mixed;boundary=---------------------9d9b7a65470a533c33537323d475531b

To: cyberdefenders@panjang.cdg <cyberdefenders@panjang.cdg>

-----------------------9d9b7a65470a533c33537323d475531b

Content-Type: multipart/related;boundary=---------------------618fd3b1e5dbb594048e34eeb9e9fcdb

-----------------------618fd3b1e5dbb594048e34eeb9e9fcdb

Content-Type: text/html;charset=utf-8

Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64

PGRpdj5USEVSRSBXSUxMIEJFIE5PIFNFQ09ORCBDSEFOQ0UuIEJFIFBSRVBBUkVELjwvZGl2Pg==

-----------------------618fd3b1e5dbb594048e34eeb9e9fcdb--

-----------------------9d9b7a65470a533c33537323d475531b--

The base64 decodes to a death threat which doesn’t have much importance. As for the rest of the email, not much information can be traced to the sender. However, we do know the domain of the sender’s email address - c0v1d.cf.

Tracing the Domain

Initially, we tried to use a DNS lookup site, namely https://securitytrails.com/, to search up the domain but to no avail. We soon hit a dead end as it returned nothing.

Pro tip: If you are stuck on a CTF challenge, come back to it an hour or two later. That’s exactly what we did.

Using a different DNS lookup site, we found a TXT record:

user=lionelcxy contact=lionelcheng@protonmail.com

Stalking Lionel Cheng

Googling his email gives us his LinkedIn account. We now know his full name.

Lionel Cheng Xiang Yi

Googling his userid lionelcxy then returns his Instagram and Carousell accounts.

Retrieving Phone Number

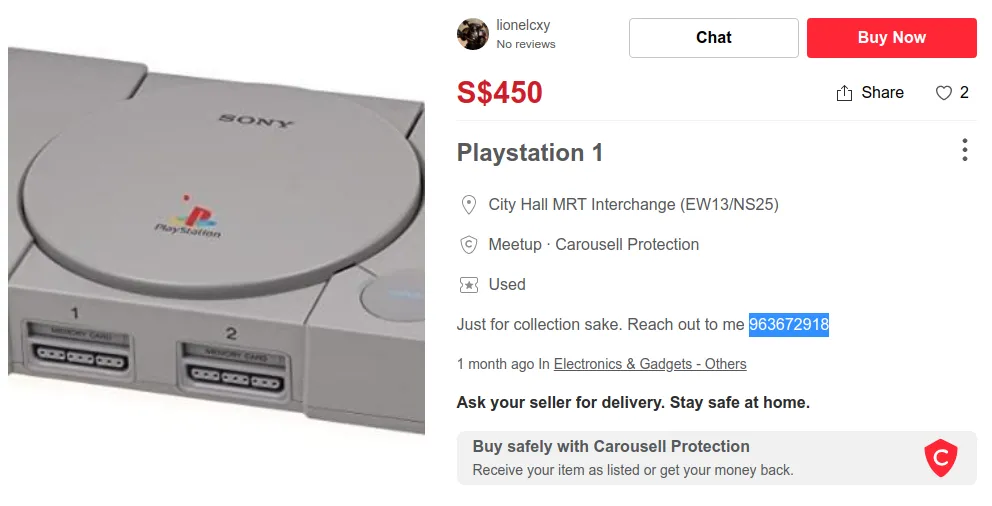

Now we just need his phone number. We turn to carousell to look for it. Carousell is a marketplace used mainly in Singapore. Having used the app before, we knew that it was not uncommon for users to put their phone number there for those that prefer to communicate through other mediums rather than the built in carousell chat.

Visiting his profile, we see a listing for a Playstation 1. And in the product description, we find his phone number.

Finding Location

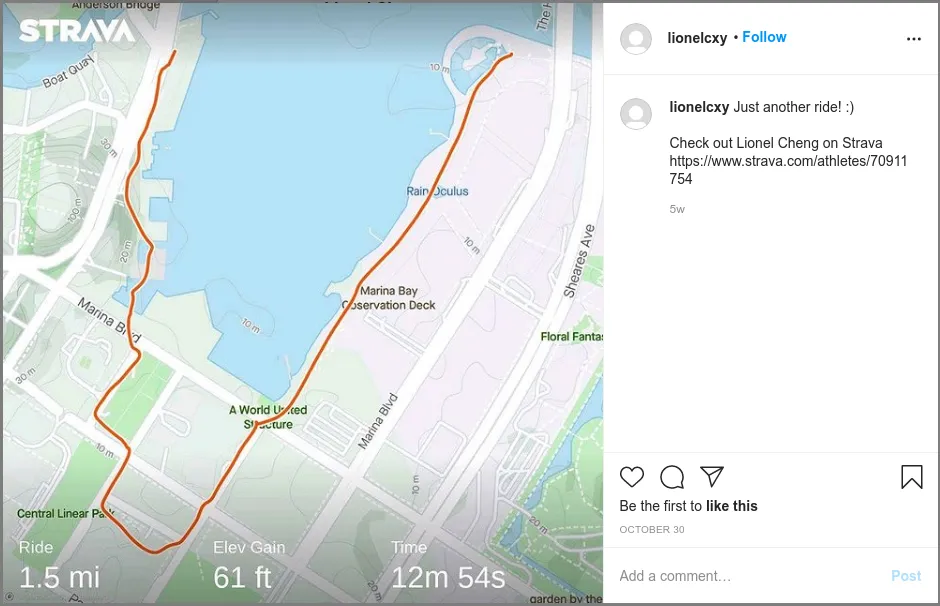

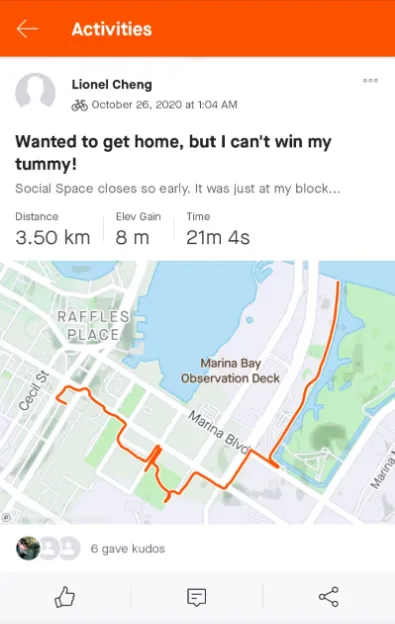

From his instagram, there are 2 posts on his account. First is him sharing his bike ride recorded using the Strava app.

And the most recent post is of a street hawker stall. More important than the picture is the location geotag which is at Lau Pa Sat a 24 hour market located at Raffles.

And the most recent post is of a street hawker stall. More important than the picture is the location geotag which is at Lau Pa Sat a 24 hour market located at Raffles.

We go on further to inspect his strava profile. Being avid runners ourselves (totally), we find his profile using the strava app and we see another one of his rides with a clue to where he stays.

Using these pieces of information, we sort of know what he did.

- He went for a bike ride

- He got hungry and wanted food

- Initially wanted to go to Social Space at his block, but it was closed

- Went to Lau Pa Sat which is close to his home to eat

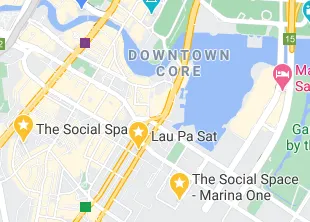

Googling the location of Social Space we see that there are 2 branches.

However we also know that Lau Pa Sat is just a few minutes away. Hence it is more likely that he was referring to the branch at Marina One rather than the one at Outram. Now we have our postal code: 018925. Our final flag is

However we also know that Lau Pa Sat is just a few minutes away. Hence it is more likely that he was referring to the branch at Marina One rather than the one at Outram. Now we have our postal code: 018925. Our final flag is

Flag: govtech-csg{LionelChengXiangYi_963672918_018925}

Who are the possible kidnappers?

Points: 1990

Solves: 3

Challenge Description

Perform OSINT to gather information on the organisation’s online presence. Start by identifying a related employee and obtain more information. Information are often posted online to build the organization’s or the individual’s online presence (i.e. blog post). Flag format is the name of the employee and the credentials, separated by an underscore. For example, the name is Tina Lee and the credentials is MyPassword is s3cure. The flag will be govtech-csg{TinaLee_MyPassword is s3cure}

Addendum:

- Look through the content! Have you looked through ALL the pages? If you believe that you have all the information required, take a step back and analyse what you have.

- In Red Team operations, it is common for Red Team operators to target the human element of an organisation. Social medias such as “Twitter” often have information which Red Team operators can use to pivot into the organisation. Also, there might be hidden portal(s) that can be discovered through “sitemap(s)”?

Information Gathering

Throughout the CTF, we see 2 organisations - COViD and Korovax. A quick Google search on Korovax reveals 2 similar websites - https://csgctf.wordpress.com/ and http://korovax.org/. By the time we started investing time in this challenge, the addendum hints had been given. Thus, we proceeded to use sitemap and gain information. I shall only put the relevant sites below.

- /never-gonna/

- Tells us to include “keywords in email”. First letter of each line spells “Rickroll”. Title of page is “Never gonna” (Irrelevant for this challenge. Used in next challenge)

- /oh-ho/

- There lies a link to the “secret social media page” http://fb.korovax.org/. And gives us more information about the passowrd that we were looking for.

-

I forgot my password to our KoroVax social media page.

I think it’s stored on our corporate page with …blue…something….communication…

Cant remember now. Would have to look through my archived tweets

- /2020/10/01/example-post-3/

- After painfully scrolling through the posts on the website, we manage to find a twitter handle @scba at the bottom of the post. Perhaps this may be our target?

Exploring “Facebook”

Note: No screenshots for this section as website was taken down before writeup was written.

We find the company’s social media at http://fb.korovax.org/. This is likely the attack point as “credentials” are required. We can simply login to the social media by creating a fake account. On the website, a user’s profile can be viewed using http://fb.korovax.org/users/<account_id>. Since account ids are given in chronological order, we view the first 10 accounts. We can then gain the following information.

- Amanda Lee

- There are many posts and comments left by her. And among those we can find

- The email for IT admin

ictadmin@korovax.org - Her Instagram @amanda.hidden

- Mention of a telegram bot named @DAViD

- The email for IT admin

- There are many posts and comments left by her. And among those we can find

- Sarah Miller

- There are many posts by her from about 2 months back. And while they do reveal some information, what stood out more was that there were more recent comments from 2h ago which seemed to be someone “impersonating” her.

- This helped us confirm that she was probably the target for the challenge

- Other accounts which we forgot

- A mention of emailing ictadmin@korovax.org and how a specific phrase is required (Irrelevant for this challenge. Used in next challenge)

Exploring Twitter

The twitter account “@scba” belongs to an actual person “Sarah Miller” who also appears in the Korovax team page. On /oh-ho/ on the Korovax website, we recall her password is “blue…something…communications”. Since Sarah Miller is actually a real person, we used a dummy twitter account for this part of the challenge. Apart from not revealing your identity, it also helps to start with fresh twitter feed with her account being the only one we followed. Searching for “blue” on the @scba twitter account, filtering by people we follow, there were only a handful of tweets that were relevant. Amongst those were: https://twitter.com/scba/status/858009339642077186.

Blue sky communications

This phrase seemed to fit the clue found on the korovax site. Entering this as her password with her email on the fb site allows us to login, confirming the flag.

Flag: govtech-csg{SarahMiller_Blue sky communications}

Rabbit Holes and Deadends

Like any CTF writeup, solving the challenge was much harder than what the writeup may suggest. These were some of the rabbit holes and deadends we encountered when we were searching. A lot of these were because we were too impulsive and immediately clicked the secret social media link without reading the rest of the page on /oh-ho/ which is arguably more important than the facebook. And many of such problems were resolved when we decided to ping admin for help.

- One of the most common ways that people accidentally reveal information is probably through pictures which objects in the background may contain crucial information

- We assumed that might have been the case for Sarah Miller and we dedcided to serach through all her media posted on twitter

- Since the korovax site had a line about keeping about conference speakers, and Sarah Miller herself has spoken in several conferences, we thought that maybe she might’ve used a personal example in her slides which could contain an old password

- This led us to searching through her slides on slideshare

- Then there were her cats butters and pixel which we though might contain a clue on her password. Since we couldn’t find relevant media on her main twitter account. So we decided to search through her cats’ twitters.

- We also looked for the password for the hidden document on the wordpress which we managed to find/guess. It was ouroboros. But unlocking only revealed a sad pepe.

![]()

- We also ventured into challenges that we’ve yet to unlocked. This included searching for Amanda’s Instagram, emailing ictadmin, looking for the telegram bot DAViD, finding korovax on google maps and calling the number. Listening in to one of Amanda’s recorded conversations.

After finishing the challenge, I guess the most important thing we learnt was to know clearly what you’re searching for. It reduces search space by a lot.

Social Engineering

Can you trick OrgX into giving away their credentials?

Points: 2000

Solves: 1

Remarks: First Blood

Challenge Description

With the information gathered, figure out who has access to the key and contact the person

Finding the Target

Since we need to contact a person, it’s most likely a phone number or email.

A quick note on sending emails during CTFs: In the wise words of Sarah Miller, “First rule of OSINT: if the subject discovers that you’re investigating them, you’ve probably failed”. Do NOT use your own email address to send the email. Instead, use temporary email sites such as https://www.guerrillamail.com/compose. For this challenge, we attempted to use such temporary emails, however, we suspect that due to black/whitelists, there was no reply. An alternative is to use a burner email address which you do not use for anything else. Now back to the challenge.

From the previous OSINT challenge “Who are the possible kidnappers?”, we identified multiple email addresses, including ictadmin@korovax.org. When sending an email to most Korovax emails such as Sarah Miller, we are replied with “Thank you for trying”. This is NOT the endpoint. It is to tell you that it is a dead end. Afterall, there is no flag.

When sending any email to ictadmin, we are replied with “Almost got it, missing something”. This means we are closer and that we need to have something in our email that ictadmin “wants”.

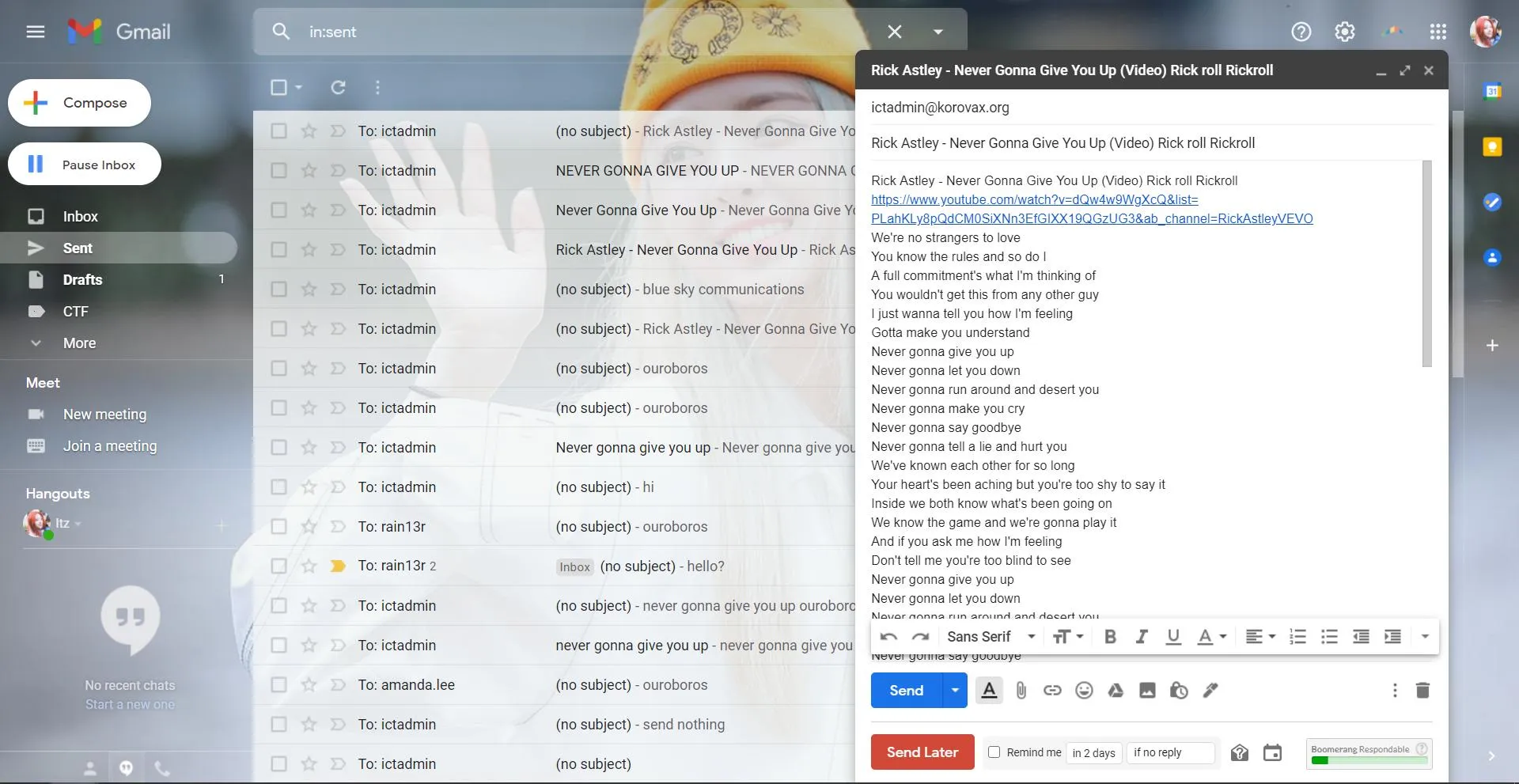

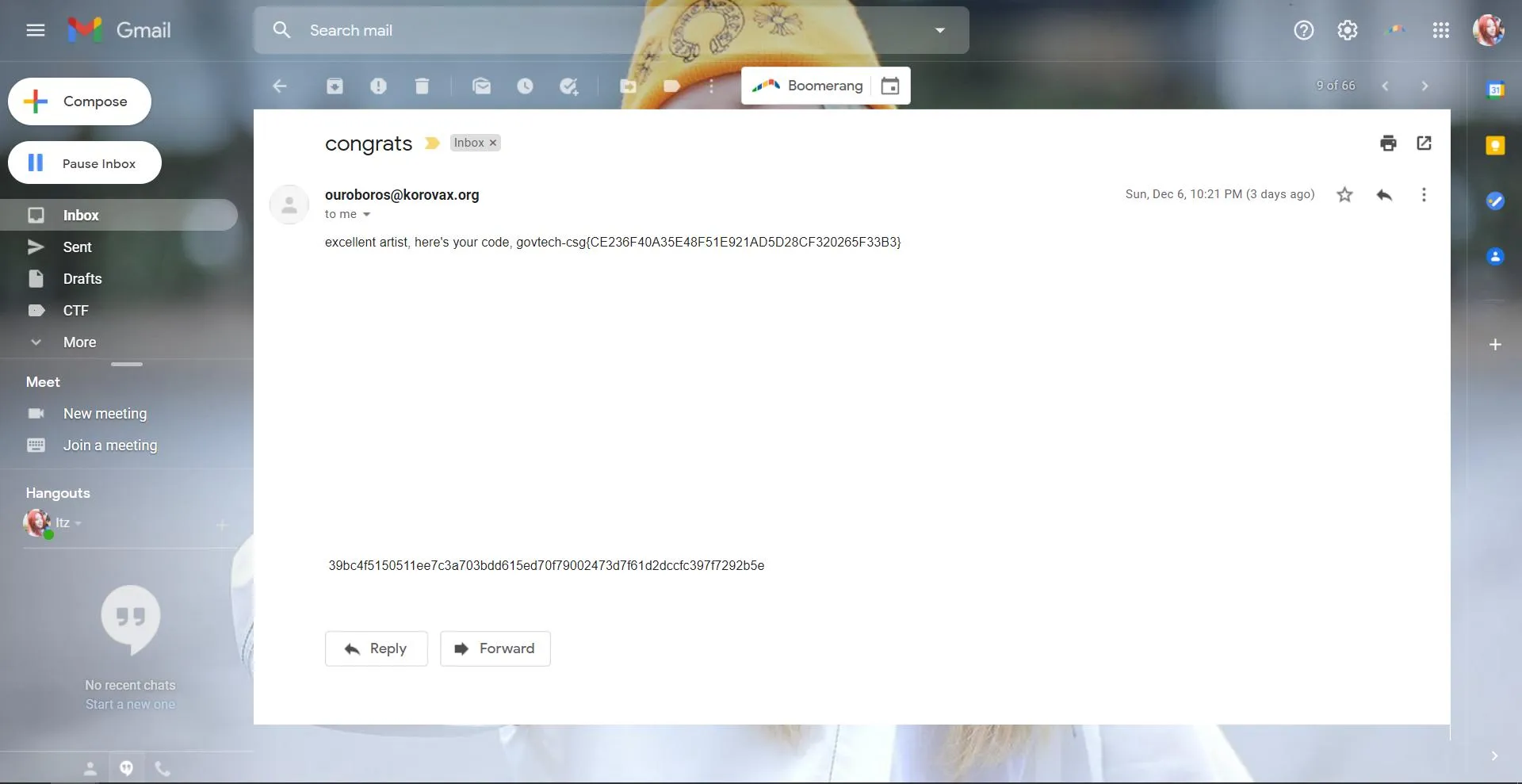

Sending the Correct Email

Recall that in the previous challenge, on https://csgctf.wordpress.com/never-gonna/, the first letter of each line in list of words forms “Rickroll”. This is a reference to the song “Never Gonna Give You Up” by Rick Astley.

Since the website tells us we need to “include” the keywords, we can basically spam a large amount of related text. Having a short amount of time left to the end of the CTF, we spammed as much related text including the full music video name, the artist, song lyrics and Youtube link. We also included the words “Rickroll” and “Rick roll”.

The bot then sends the flag to us with a hint for the next social engineering challenge which we had no time to do.

After the CTF, we proceeded to try shrinking our “payload” to find the right answer. The bot was specifically looking for the word “Rickroll”.

Flag: govtech-csg{CE236F40A35E48F51E921AD5D28CF320265F33B3}

Reverse Engineering

An invitation

Points: 981

Solves: 11

Challenge Description

We want you to be a member of the Cyber Defense Group! Your invitation has been encoded to avoid being detected by COViD’s sensors. Decipher the invitation and join in the fight!

Starting off

Looking at index.html, we open it in the browser, but nothing seems to show up on the page. We view the browser console to see an undefined variable error message in invite.js, imported through a <script> tag. For jquery-led.js, it appears as decently well written and formatted code, with the author credited and license mentioned as well. After a little Googling, we quickly discover that it is an open-source plugin. We can conclude these are likely not needed to be reversed, and instead it is invite.js that does, being related to the challenge name as well.

Breaking down invite.js

Rather than handling the mess of obfuscation entirely manually, we can put it into an automatic formatter. For JavaScript, we can just use beautifier.io. The beautified code looks like this:

try {

canvas = document["querySelector"](".G");

gl = canvas["getContext"]("webgl");

gl["clearColor"](0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0);

gl["clear"](gl.COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

shade = canvas["getAttribute"]("shade");

ctype = canvas["getAttribute"]("type");

cid = canvas["getAttribute"]("id")["slice"](5, 7);

gl["KG"] = window[shade + cid + ctype];

} catch (err) {}

var _0x55f3 = [

"||||||function|var||hhh||||for|charCodeAt|if|length|eee||uuu||mmm|||custom|fromCharCode|String|vvv||ggg|location|catLED|type||color||rounded|font_type|background_color|e0e0e0|size|return|zzz|FF0000|value|seed|yyy|rrr||ooo|slice|ttt|false|window|else|you|iii|let|YOU||compare|0xff|||23|re|hostname|console|||57|protocol|file|54|log|max|Math|98|requestAnimationFrame|true|0BB|00|88|09|0FZ|02|0D|06HD|03S|31|get|new|Image|Object|defineProperty|id|unescape|invited|2000|pathname|const|ech||setTimeout|WANT|WE|custom3|custom2|INVITED|RE|custom1|debugger|1000|invite|the|accepting|alert|Thank|indexOf|go|118|3V3jYanBpfDq5QAb7OMCcT|leaHVWaWLfhj4|atob",

"toString",

"replace",

"x=[0,0,0];1C Y=(a,b)=>{V s='';d(V i=0;i<1e.1d(a.g,b.g);i++){s+=q.p((a.e(i)||0)^(b.e(i)||0))}F s};f(u.19=='1a:'){x[0]=12}S{x[0]=18}f(Y(R.u.14,\"T'13 1z!!!\")==1y(\"%1E%1j%1q%17%1p%1o%1n%1m%1l%1i@M\")){x[1]=1k}S{x[1]=1r}6 K(){7 j=Q;7 G=1t 1u();1v.1w(G,'1x',{1s:6(){j=1h;x[2]=1b}});1g(6 X(){j=Q;15.1c(\"%c\",G);f(!j){x[2]=1f}})};K();6 N(J){7 m=Z;7 a=11;7 c=17;7 z=J||3;F 6(){z=(a*z+c)%m;F z}}6 U(h){P=h[0]<<16|h[1]<<8|h[2];L=N(P);t=R.u.1B.O(1);9=\"\";d(i=0;i<t.g;i++){9+=q.p(t.e(i)-1)}r=1Z(\"1X//k/1Y=\");l=\"\";f(9.O(0,2)==\"1V\"&&9.e(2)==1W&&9.1U('1D-c')==4){d(i=0;i<r.g;i++){l+=q.p(r.e(i)^L())}1S(\"1T T d 1R 1Q 1P!\n\"+9+l)}}d(a=0;a!=1O;a++){1N}$('.1M').v({w:'o',y:'#H',C:'#D',E:10,A:5,B:4,I:\" W'1L 1K! \"});$('.1J').v({w:'o',y:'#H',C:'#D',E:10,A:5,B:4,I:\" \"});$('.1I').v({w:'o',y:'#H',C:'#D',E:10,A:5,B:4,I:\" 1H 1G W! \"});1F(6(){U(x)},1A);",

"w+",

];

(function (_0x92e4x2, _0x92e4x3) {

var _0x92e4x4 = function (_0x92e4x5) {

while (--_0x92e4x5) {

_0x92e4x2["push"](_0x92e4x2["shift"]());

}

};

_0x92e4x4(++_0x92e4x3);

})(_0x55f3, 0x65);

var _0x3db8 = function (_0x92e4x2, _0x92e4x3) {

_0x92e4x2 = _0x92e4x2 - 0x0;

var _0x92e4x4 = _0x55f3[_0x92e4x2];

return _0x92e4x4;

};

var _0x27631a = _0x3db8;

gl["KG"](

(function (_0x92e4x5, _0x92e4x8, _0x92e4x9, _0x92e4xa, _0x92e4xb, _0x92e4xc) {

var _0x92e4xd = _0x3db8;

_0x92e4xb = function (_0x92e4xe) {

var _0x92e4xf = _0x3db8;

return (

(_0x92e4xe < _0x92e4x8

? ""

: _0x92e4xb(parseInt(_0x92e4xe / _0x92e4x8))) +

((_0x92e4xe = _0x92e4xe % _0x92e4x8) > 0x23

? String["fromCharCode"](_0x92e4xe + 0x1d)

: _0x92e4xe[_0x92e4xf("0x0")](0x24))

);

};

if (!""[_0x92e4xd("0x1")](/^/, String)) {

while (_0x92e4x9--) {

_0x92e4xc[_0x92e4xb(_0x92e4x9)] =

_0x92e4xa[_0x92e4x9] || _0x92e4xb(_0x92e4x9);

}

(_0x92e4xa = [

function (_0x92e4x10) {

return _0x92e4xc[_0x92e4x10];

},

]),

(_0x92e4xb = function () {

var _0x92e4x11 = _0x92e4xd;

return _0x92e4x11("0x3");

}),

(_0x92e4x9 = 0x1);

}

while (_0x92e4x9--) {

_0x92e4xa[_0x92e4x9] &&

(_0x92e4x5 = _0x92e4x5[_0x92e4xd("0x1")](

new RegExp("\b" + _0x92e4xb(_0x92e4x9) + "\b", "g"),

_0x92e4xa[_0x92e4x9]

));

}

return _0x92e4x5;

})(_0x27631a("0x2"), 0x3e, 0x7c, _0x27631a("0x4")["split"]("|"), 0x0, {})

);

Other than formatting the code, the beautifier also did some variable substitutions for us, saving us some effort. To summarise what the code does:

-

trysettinggl.KGto a globalwindowvariable - declare a (rather large) string array variable

_0x55f3 - some array methods on the above string array

- declare a helper function, assigned to both

_0x3db8and_0x27631a - call

gl.KGas a function on an IIFE (immediately-invoked function expression)

The undefined variable error found in the browser console when opening index.html, is in fact for gl, which means the try block had failed. The attributes of some elements provided in DOM (Document Object Model) of index.html don’t match up exactly with what invite.js requires. As there are only a limited number of possible global functions, in window, we can try to figure out what the function gl.KG was intended to be. A good way to do this is to look into the IIFE that was called as the argument of gl.KG.

Analysing the IIFE

Before starting, we remove the try block, and put the IIFE into console.log, so we can run the Javscript as we wish. Rather than analysing from top to bottom, we trace backwards starting from the return value, _0x92e4x5. The only places that this variable appears in the IIFE are as the first parameter, in an assignment in the while loop just before returning, and of course in the return value itself. We don’t need to deal with the rest of the IIFE. (Though note that during the actual CTF, I did reverse much more of the code to get a good handle on what it really does.)